Written by guest author Kenny Fennell. Kenny is a consultant with WSP’s New Mobility Group. His work focuses on emerging mobility pilots, policy, and planning. Prior to this role, he worked in the City of Detroit’s Office of Mobility Innovation. Views shared here are his own.

Public and private sector stakeholders are realizing that Mobility as a Service (MaaS) is much more than an app. In fact, delivering MaaS relies more on out-of-app, rather than in-app, features. Delivering these features across the network of diverse stakeholders involved in MaaS will require a new way framework: Systems Thinking.

First, An Intro to Systems Thinking

Systems Thinking is an analytical approach that considers how a system’s individual components interrelate both through time and within the context of a larger system. In part, Systems Thinking is driven by the philosophy and tactics of fields such as Human-Centered Design, Design Thinking, Service Design, Customer Experience, and related fields. We can narrow Systems Thinking down to two primary parts: 1) Component Dynamics: Understanding how an individual component delivers its value proposition to customers through the combination of front-end customer-facing and back-end non-customer facing operations and 2) System Dynamics: Understanding how individual components interrelate both to other components and the greater system of which they are a part. It is easy to see how Systems Thinking is necessary to deliver MaaS with various public and private components requiring a number of services on the front- and back-end.

The Individual Components and Overarching System of Mobility as a Service

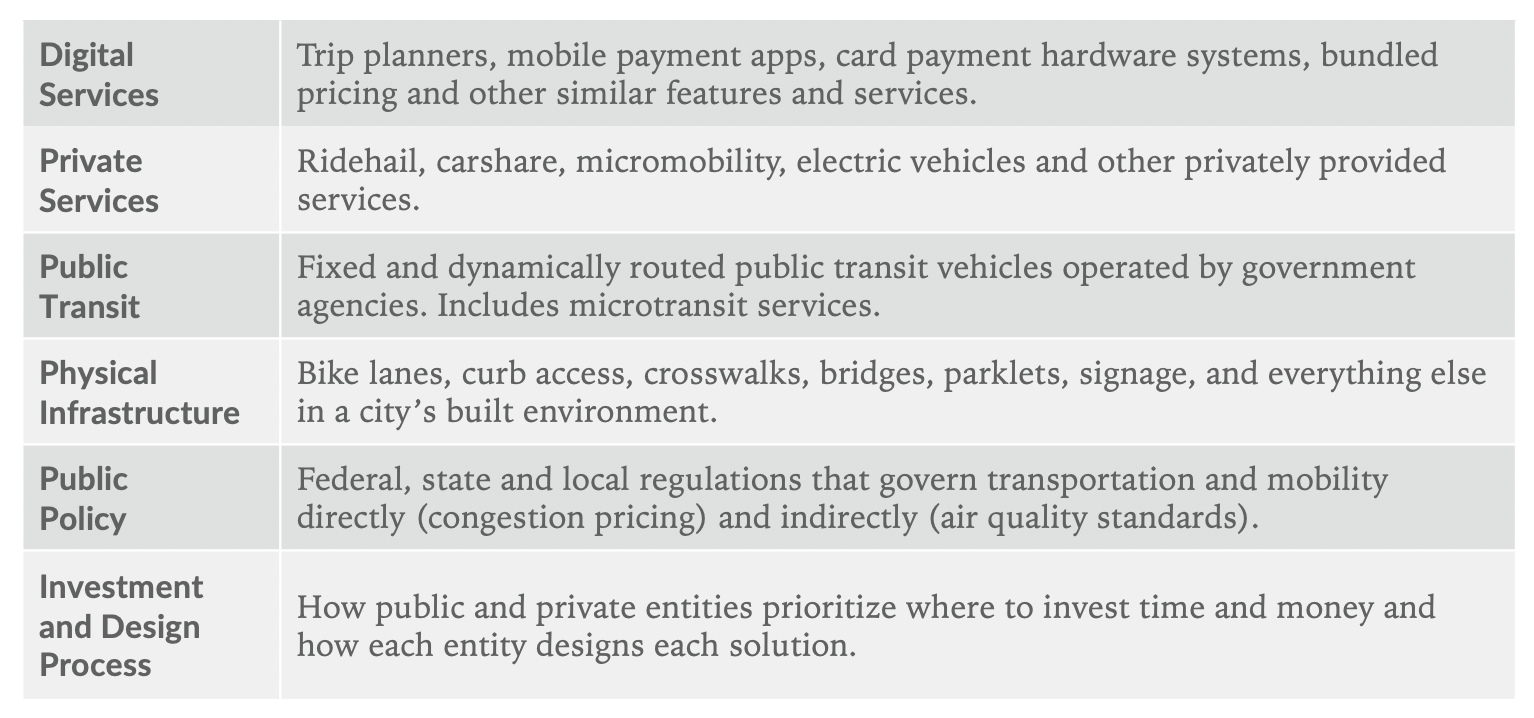

The individual components of MaaS are categorically defined as follows, ranked in order of least to most foundational to delivering MaaS’ ultimate value proposition: seamless movement, anytime, anywhere (i.e. freedom):

Within these categories, there are individual components and entire systems in and of themselves. However, this article focuses on how the above components categorically interact with each other as part of the MaaS System.

MaaS is the system of these components working seamlessly together to deliver end-user freedom of movement across a geographic area, over time, regardless of mode or the trip’s purpose. In a complete MaaS system, I would be able to seamlessly ride my bicycle to my bus stop during my morning commute, walk to a carshare and pick up groceries on the way home, and take a ridehail trip back home after visiting a friend across town. However, this is not true today.

Viable Components Are Needed for a Viable System

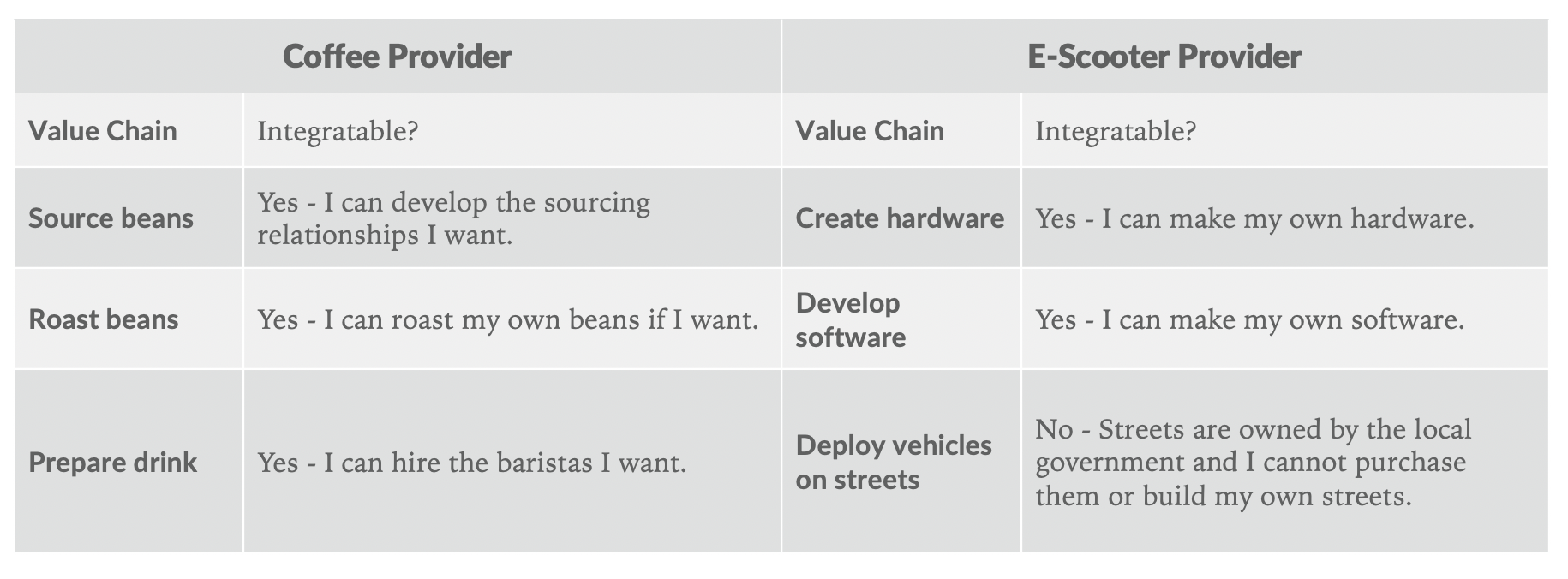

To deliver MaaS, each component must deliver its individual value proposition while enabling the value propositions of other components in the system. This is essentially a value chain. In coffee, for example, to serve a cup of coffee to my customer, I must source coffee beans, roast the beans and create the drink. For an e-scooter company, to give my customer a ride, I must create the hardware, develop the software, and deploy my vehicles on the street. In both cases, the components rely on each other to deliver the service to the end-user. However, the components of the coffee system are easier to vertically integrate, if necessary, relative to the components of the e-scooter company. In coffee, I can integrate a roasting operation if suppliers do not meet my standards. However, my e-scooter company is stuck with the quality of streets provided by the local Department of Public Works whether or not they provide the safe riding experience I need to be a successful e-scooter company.

Thus, MaaS components and the MaaS system significantly rely on other components out of their control to deliver individual and system value propositions. Some unfortunate examples:

- A city can launch a bikeshare service and do all it needs to deliver the service to individual customers. However, the service will be unable to deliver its value proposition if the foundational physical infrastructure fails to provide safety for end-users. Fixing this problem relies on State and Local governments updating their investment and design process to prioritize safety for people on their streets.

- Without a robust transportation system, more people will use personally owned vehicles and increase congestion. Given the sunk-cost effect of personal vehicle ownership in which people who own cars tend to make most of their trips by car, people are less likely to use a new shared mobility service to travel. Again, unless policy is improved to prioritize shared modes and fund transit to the level required to deliver its value proposition, the MaaS system and its components suffer.

- I can launch a MaaS app to coordinate complex journeys across a variety of shared modes. However, if carshare, microtransit, bikeshare and other services aren’t available in my city, the MaaS app serves no value as there are no services to coordinate or payment plans to bundle.

This is where Systems Thinking enables MaaS innovation. Professionals must not only deliver the value proposition of the component for which they are responsible, they must recognize how the choices they make when designing their component will affect the value propositions of other components and the entire MaaS system. For example, creating a car-free 14th street in NYC resulted not only in faster bus speeds, but also increased bikeshare ridership.

Delivering MaaS

The component level work is happening across the United States. Governments are investing in their components as we see with Pittsburgh’s Bike+ Master Plan (Physical Infrastructure) and Metro Transit’s Bus Rapid Transit plans (Public Transit). Meanwhile, the transit industry is facing labor shortages and the transportation sector is rapidly becoming the highest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions with California seeking legislative solutions through SB-100: Renewable Portfolio Standard Program and SB-1014: The Clean Miles Standard (Policy).

Similarly, private companies are doing their part. Autonomous vehicle companies like Cruise and micromobility companies like Bird are continuously evolving their vehicles to provide rides (Private Services) while Pigeon is exploring the business model of crowd-sourced transit information and Miles is creating a transportation reward programs (Digital Services).

Bird clearly understands these interrelated dynamics given their push for safe infrastructure, but will each company in the MaaS system have such a direct lever to pull? As an investor or founder in urban transportation and mobility, you must believe that, in time, interrelated system problems will be solved and customers will value both the features of individual components and the MaaS system as a whole.

Two ways in which we could see this happen:

- Governments will increasingly adopt human-centered design approaches in their policymaking and budgetary decisions. This will enable governments to understand how their decisions might affect individuals, businesses, and the system itself and incorporate such effects into their decision-making process.

- Public-Private Partnerships will increase as the private and public stakeholders realize they need mutual investment to unlock the shared benefits of their efforts. The Federal Transit Administration already does this through its Accelerating Innovative Mobility grants. The safe streets that micromobility companies and residents desire could be created through the evolution of these partnerships.

These developments will enable Systems Thinking because they force each stakeholder to consider those that might not be explicitly considered in their current investment and design processes. This will empower each stakeholder to deliver what is necessary not only for their component’s value proposition but also the value propositions of other components and the overall MaaS system. In the short-term, startups and investors will likely focus on the most viable use cases to slowly build their individual MaaS components: closed systems and controlled environments (For an analogous use-case, see Loup portfolio company, Outrider). In the long-term, companies and governments that learn how to engage in a constructive way with their cross-sector counterparts using Systems Thinking will likely generate more financial and non-monetary benefits overall than those that take a more competitive approach to achieve walled-garden like financial benefits at the expense of the greater system and people within it.