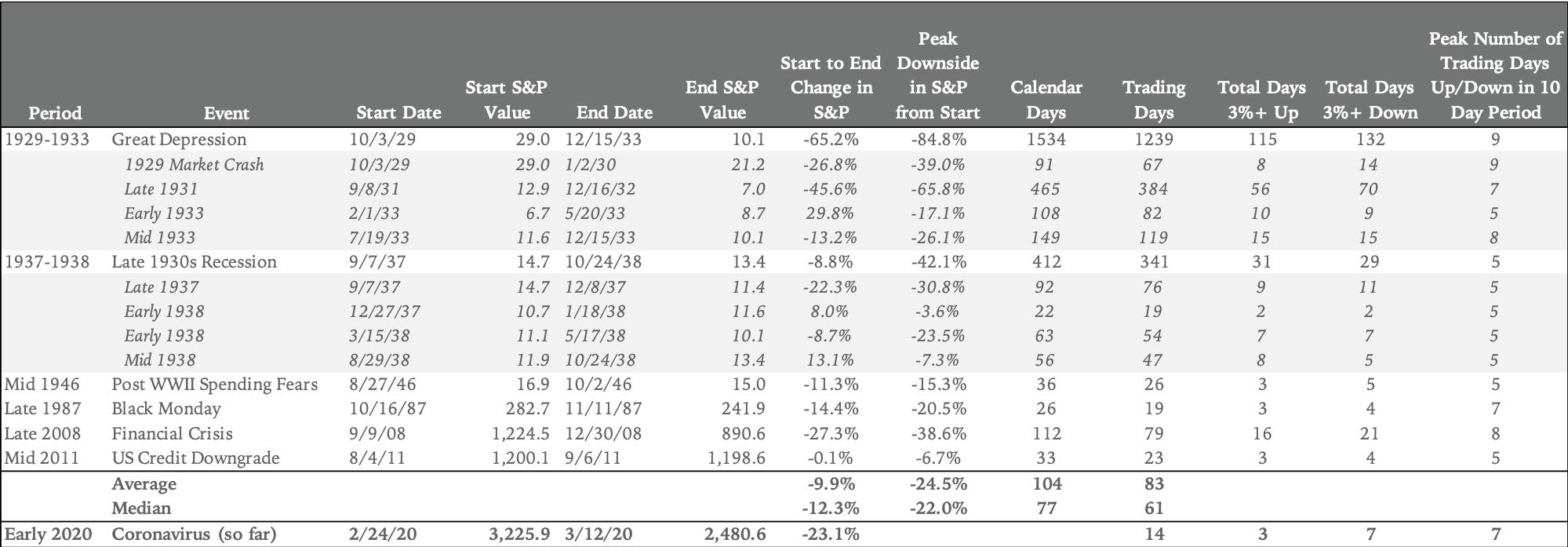

Over the past 10 trading days, the S&P 500 has been +/- 3% seven days. Only six other periods in recorded history have had similar levels of stock market volatility.

We looked at the last 100 years of daily S&P 500 movements for 10-day trading periods with at least five days of +/- 3% moves. Aside from the current market, the six periods that matched our criteria were:

- The Great Depression from 1929-1933 (multiple times)

- The 1937-38 Recession (multiple times)

- The 1946 Post-War Correction

- The 1987 Black Monday Crash

- The Financial Crisis in 2008

- The 2011 US Credit Downgrade

No other period has had five +/- 3% S&P 500 trading days in a 10-day period; not the dotcom crash (although the Nasdaq likely did) nor any of the 11 recessions prior to the Financial Crisis of 2008 back to the 1937-38 recession.

As Benoit Mandelbrot (and others) realized, volatility clusters. For the study above, we classified the length of the volatility period as starting with the first day in the eventual string of five or more +/- 3% days and the end as the last day in the string. In other words, at the start of the volatility period, there were no days over the prior 10 with a +/- 3% move until the one that started an eventual chain that resulted in five or more such days in the 10 day period. Similarly, we marked the end of the volatility period as having no +/- 3% days in the prior 10.

Looking at the data, both the Great Depression and the 1937-38 Recession periods had several well defined periods of volatility per our definition. We’re showing them both grouped together including some breaks in volatility periods per our definition given that the same macro event would seem to be the primary source of the volatility periods. For the 2008 Financial Crisis, there remained some volatility after the period we noted, but the markets never returned to a five day or greater string of +/- 3% days.

So, what does it mean? A few thoughts:

- First of all, no simple analysis can explain a complex adaptive system like the stock market, which is, in many ways, a forward-looking assessment of another complex adaptive system, the economy. We can assume that over the past few weeks, the core ingredients that have led us to where we are today are some combination of coronavirus, oil, a lot of people waiting for the end of the business cycle, perhaps some election uncertainty, a good deal of fear, disappointing government response, and probably several other things we’ve failed to mention. Given that backdrop, we don’t know how to call the bottom because we don’t know which of those known or unknown ingredients could remedy the markets.

- That said, we do know that the way the market has acted over the past few weeks is unique from a historical perspective, and that can help us at least form a basic framework to consider the big questions about the state of the market, even if we don’t understand all the components going into the movements.

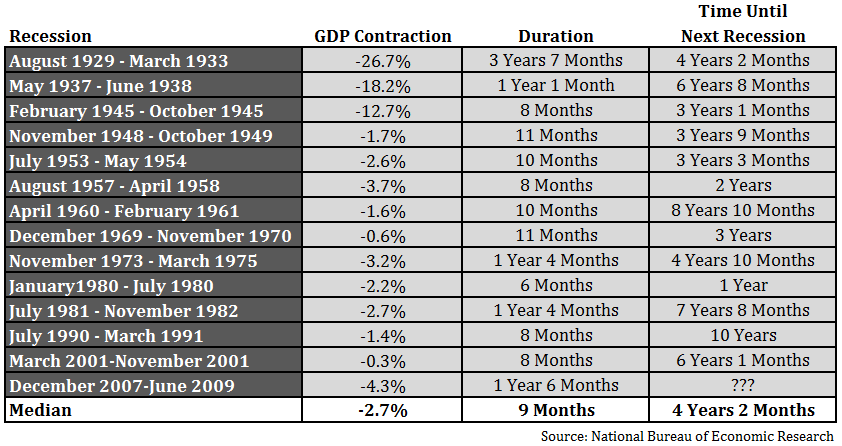

- Amongst the six periods of comparable market volatility, there appears a clear dichotomy: severe economic impact and modest to minor economic impact. The Great Depression, the 1937-38 Recession, and Financial Crisis fit in the former category. The Post WWII fears, 1987 Crash, and 2011 US Credit Downgrade seem to fit in the latter category. It feels like the market is deciding where the current economic situation fits. We’re already at the average/median of the peak downside to the S&P from the other six events. If we see a continued markdown over the next week or two, it would seem to be a strong signal that the market expects a more significant economic impact rather than a modest one.

- The fundamental question we think investors should ask themselves is does this environment feel closer to a major economic event, perhaps something on the order of a depression, or a more modest one? A major economic event would seem to suggest a strong 12-18 month recession based on recent history. The modest to minor scenario would likely assume nine months or less.

For businesses, the best course of action in uncertain times like this is to prepare for the worst and hope for the best. In investing, the same advice is sensible, but we would add a caveat which is, if you have strong conviction in times of uncertainty, then don’t just prepare for the worst, try to be right. While there is undoubtedly more volatility to come, we think the current market dynamic will create a fertile environment for long-term, growth-oriented investors like ourselves and our limited partners.