Smartphones have made us superhuman by bestowing on us the intelligence of the world’s information at our fingertips persistently; however, few would disagree that our omnipresent devices also create undesirable outcomes. We spend so much time on our phones that we ignore the real world and real people around us. Studies have suggested that technology addiction contributes to unhappiness and higher rates of suicides because we have fewer meaningful relationships.

At Loup, we often debate the effects technology has on humans. While we agree that no technology is purely good or evil — all things come with tradeoffs — I argue that technology doesn’t create new problems per se, it amplifies existing problems inherent to the human psyche. The point of technology is to augment the human experience, so it would stand to reason that such augmentation will happen in both positive and negative ways.

Humans are biologically incentivized to seek pleasure and avoid pain. This is the basis for not only our survival instinct, but also all addiction, technology included.

Defining the Problems Caused by Tech Addiction

The research says that technology makes us unhappy and most attribute that to our smartphones; however, it isn’t our smartphones alone that make us unhappy, it’s the information we consume on our smartphones. The device is a conduit for content. On Instagram, we’re bombarded with beautiful people living perfect lives. On Twitter, we’re bombarded with short, angry arguments about politics among other things. On YouTube, we’re bombarded with endlessly interesting videos that keep playing until we stop them.

The constant stream of notifications and information we receive gives us a pleasurable hit of dopamine, entices us to return, and feeds our addiction even though it isn’t constructive or healthy. There seem to be three core content-related mechanisms that contribute to unhappiness: inferiority, anger, and distraction.

- Inferiority. The idea of “Keeping up with the Joneses” has been a human psychological reality probably since we were jealous of our neighbor’s four-bedroom cave in the Stone Age. Technology has brought the world closer. On some platforms, Instagram in particular, everyone seems beautiful, glamorous, and rich. We feel like everyone is our neighbor, and we have to keep up with all of them, which is impossible. We also risk feeling left out if we see our friends having fun, and we’re not there.

- Anger. Unfortunately, anger is more engaging than rational discussion. When we’re angry, we feel the need to respond and defend our opinions. Then we share that response with everyone we know so they can respond too. If the world agrees with us, our anger is justified. If the world disagrees with us, we engage in moral combat and get even angrier. Because media platforms monetize primarily through advertising, which is sold by engagement, facilitating discussion that is based on emotion instead of logic is more profitable.

- Distraction. Distraction is a direct byproduct of the aforementioned search for pleasure. Every time we get a notification or the next auto-play video starts, it’s a chance for pleasure, and if we miss out, that could be perceived as pain. By responding to every notification, we can’t focus, which causes procrastination, poor performance, and stress.

We Can’t Rely on Tech Giants to Fix Tech Addiction

To meaningfully reduce technology addiction, Apple, Google, and Facebook could just eliminate the stream of notifications we get from their products. We don’t need to know every time someone posts a new picture on Instagram or see the stories curated for us from Google News on Chrome or even get a new email.

Unfortunately, eliminating apps or notifications would hamper the paramount metrics to each of these businesses: device sales, platform engagement, and paying customers. These companies are some of the most socially conscious companies in the world, but they’re still beholden to shareholders and employees that survive on profit. While Apple, Google, and Facebook are beginning to offer tools to better understand how much we use their devices and services, those companies can’t viably fix technology addiction because their businesses prevent them from doing so.

So, What Do We Do About Tech Addiction?

As with anything deemed a problem by society, particularly when addiction is a risk, there is the potential for government regulation. We tried prohibition in the early 1900s. More recently, we’ve had attempts to limit the size of soft drinks in New York.

Protecting people from themselves never seems to work well. Freedom and safety are an eternal tradeoff. Most rational individuals would rather not have others make decisions for them in the name of their safety but at the cost of their freedom. We want to decide what’s best for ourselves, even if we choose incorrectly.

The real answer to solving technology addiction is the answer to sustainably solving most problems: innovation spurred by capitalism. A new group of businesses needs to emerge that gives us the choice to help ourselves and rediscover the benefits of disconnection.

Dieting may be the most helpful analogy here. In the US, many of us have poor diets either on occasion or frequently. Few of us have the discipline to eat well for long periods of time to optimize our health. When we gain too much weight, we pay for a personal trainer or a diet program or a book or an app to get us back on track.

We are all severely overweight with how much we use technology, and we need a diet.

Solutions

We see two types of solutions for solving tech addiction: software-based solutions and experience-based solutions. Software-based solutions are software tools that help us understand how much time we’re spending using technology and even block us from using certain technology. Major tech companies are providing some of these tools now like Apple on iOS with Downtime. Third party companies provide even more aggressive versions of time-management apps. Experience-based solutions are rarer, but examples include one-on-one counseling for addiction and locations that ban smartphone use.

To date, solutions to tech addiction are posed as limiting a negative. We track or limit how much time we spend. However, just as we noted with government intervention, “don’t do this because it’s bad for you” is a poor sales pitch. Companies that deliver meaningful solutions to address tech addiction need to sell benefits first and may not even talk about tech addiction.

People pay for diets and exercise because there are real physical, mental, and social benefits to being healthy and looking better. People will pay to disconnect from technology for two core benefits: happiness and prosperity. Happiness is most connected to the elimination of feelings of inferiority and anger. Prosperity happens through focused effort that avoids distraction.

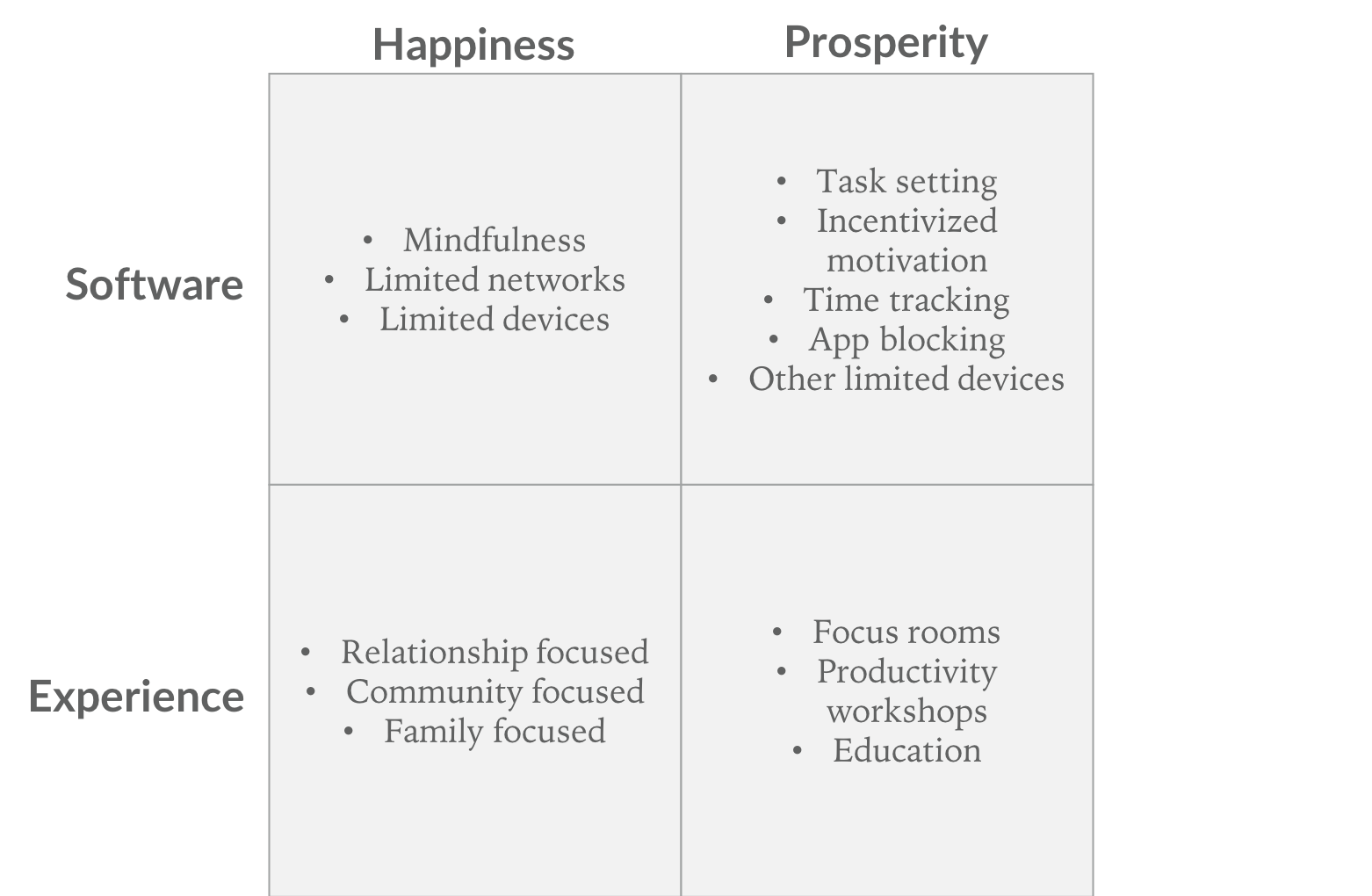

In summary, we see two types of solutions: software-based solutions and experience-based solutions, each able to provide two core benefits: happiness and prosperity. We can think of the opportunities in managing tech addiction in a matrix:

The opportunities listed in each quadrant are examples and non-exhaustive. There are ideas in each category we’ve seen or would like to see. The best ideas aren’t likely included, but here are some additional thoughts on a few of the concepts above that we think are the most interesting:

- Limited devices. Putting limitations on the devices we use can circumvent addictive behavior at the source. This would happen at the OS layer; however, as noted above, it’s unlikely Apple and Google put true restrictions beyond the tracking and alert features they’ve implemented recently. Phones similar in function to ones from a decade ago can make sense. A phone that is only capable of making calls, texting, and a handful of other features may help increase happiness. Laptops without internet, or with heavily restricted internet access established at the OS layer, can offer focused productivity that leads to prosperity. If someone can’t engage in addictive behavior, they won’t. At least not on their restricted devices.

- Incentivized motivation. Incentives drive action. The incentive of excitement you get from the ding of a notification keeps us coming back to our phones, but we can turn that concept around to make us stop using our phones. An application could provide a user frequent alerts to get back to work or put the phone down if they’ve been using it for 10 minutes or more. Taking the idea further, there could be some financial or other incentive (maybe the user escrows some money toward buying something they want) if they hit their goal. By breaking the spell of or adding friction to whatever non-productive activity we’re engaged in, we have an opportunity to exercise willpower to channel our focus elsewhere. We may not be able to make productivity as addicting as Instagram, but we should be able to get close.

- Focus rooms. Every coworking space and office should have a room where phones are prohibited and internet is restricted — a sort of productivity oasis amidst the office desert of distraction. Enforcement is the key problem to solve here, which might require a monitor to make sure that customers aren’t loose with adherence to device restrictions. A focus room can also serve as a social proof reminder to others, encouraging them to act to curb their addiction to being connected.

Conclusion

Our phones aren’t going away; neither are our social networks. A full technological lobotomy isn’t even desirable since it would remove the good with the bad. Humans always find ways to evolve and the solution to tech addiction will be no different. Ingenuity spurred by the freedom of markets will create various solutions that help us manage tech addiction. People that use those solutions to effectively curb negative habits will end up happier and more prosperous than others, just like it’s always been. How’s that for incentive?

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest or may invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we may write about companies that are in our portfolio. As managers of the portfolio, we may earn carried interest, management fees or other compensation from such portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making any investment decisions and provided solely for informational purposes. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections and the content on this site should not be relied upon. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.