What’s my company worth?

What makes you special?

The two questions are inextricably intertwined. The more special your value add, the more your company’s potential value. It’s true at the individual level too. The value of your time or effort for another person is relative to how special the value you create for them.

The two questions collided for me in a fun way this weekend. A founder in our network asked how he should value his company because he knows that what makes Deepwater special is our span of expertise across early-stage venture to late-stage venture to public market investing.

Uniqueness often comes from combining things that don’t go together (h/t Naval Ravikant) but living in our world of early stage and public market investing makes the advantage clear. We get a perspective that peers who focus only on one segment or another don’t.

By spending a large part of our days interviewing smart early-stage founders about where they see the world going, we get investment ideas that are relevant to publicly traded companies. And by immersing ourselves in how sophisticated public investors value companies — the ultimate destination for the biggest winners in venture — we earn a perspective for what really has to happen for a venture investment to create a great outcome based on fundamentals rather than luck.

So, given that perspective, what’s a company worth?

Here’s the Deepwater valuation playbook for founders on the road to building a sustainable private enterprise or getting ready to go public in a few years. Founders of earlier stage ventures can learn some useful tips too.

Deepwater’s Six Rules of Valuation

Rule 1: A company is worth the sum of all the cash it will generate for owners in the future discounted back to the present.

The end. Playbook over.

If only it were that simple. Academically, the value of a company in any given point in time is value of its future cash flows discounted back to the present, but the reality of the present is much messier.

Many companies, especially early-stage ones, don’t generate any revenue. It’s hard to make estimates about how much cash a company might generate for the next 10+ years when it doesn’t even sell anything yet. Instead of discounted cash flow models (DCFs), many investors use simpler tools like revenue, EBITDA, or even user multiples to set value when detailed financial information is lacking.

It’s worth noting, not a jab but as a feature of markets, that some investors use the simple valuation tools out of laziness, and many use the tools because it’s what everyone else uses. Even if those simple multiples are less precise than more complicated DCFs, they may better explain how other buyers in the market will think about prices since they are the most common methodology.

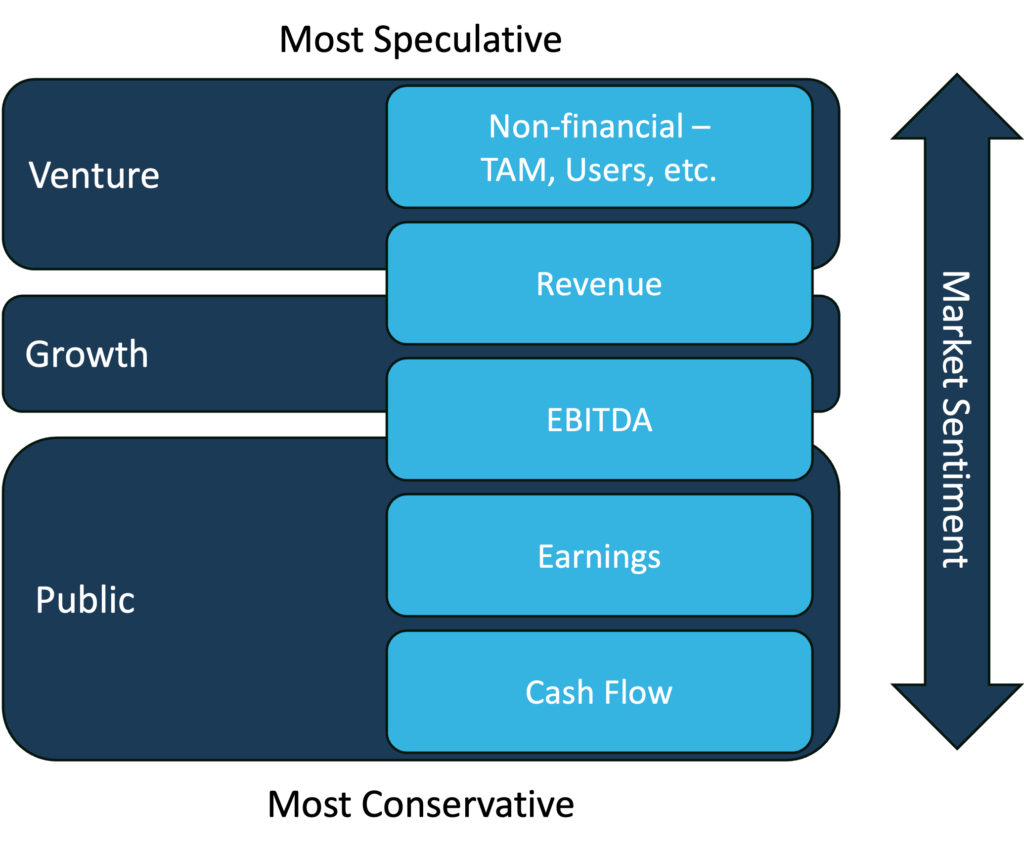

As a simple framework for thinking about valuation, consider three factors: methodology, company stage, and market sentiment.

The five major methodologies for setting valuation are a multiple on non-financial metrics like users, revenue, EBITDA, earnings, and cash flow. Investor desire to use these different methodologies depends on the stage of the company and the sentiment of the market.

Venture investors in early-stage companies often need to rely on abstract elements of a company to set a value. Growth investors look at revenue or EBITDA. Public investors look at earnings and cash flow. For common understanding, cash flow means free cash flow (operating cash flow less capital expenditures).

Valuing a company on something non-financial is the most speculative form of valuation, which correlates with the intended nature of venture investing. Valuing a company on cash flows is the most conservative form of valuation and a reasonable expectation for buy stock of a publicly traded company where the ultimate destination will be an expectation of profits.

The market sentiment factor is where things get interesting.

When market sentiment is bubbly, investors that might traditionally use earnings or cash flow as a basis for valuation may start using EBITDA or revenue. When market sentiment is full of fear, investors that might have gotten comfortable with TAM or revenue-based valuations might instead choose to hold cash because they think they need to see EBITDA now.

This framework serves as a model for how investors think about valuation with simple metrics, but it’s still all about cash flow in the end.

Rule 2: Everything is a DCF.

A revenue multiple is an abstract form of a DCF. So is a user multiple. So is an EBITDA multiple.

A company might get a higher or lower revenue multiple relative to peers based on factors that would be defined in a DCF: growth, margin expectations, and terminal value (duration of the business).

Companies with high multiples often come with high revenue growth, strong long-term margin profiles, and an assumption that the business will continue to generate cash flows long into the future. Good growth, strong margins, and persistence mean the investor will get more cash flow returned to him over time, so he should be willing to pay a higher multiple against the business’ near-term state than slower growth, lower margins, and questionable duration businesses. Those businesses get lower revenue, EBITDA, or other multiples.

Understanding how the market views businesses on a simple multiple basis is good. Defining the underlying assumptions that go into a multiple-based valuation is better because a valuation is a demand for future performance that investors underwrite, and equity issuers have to deliver.

Rule 3: A valuation is a demand for some future performance.

You reach this logical conclusion by inverting the idea of a DCF. If a DCF establishes the value of a company given a discounted summation of future cash flows, then a valuation establishes the stream of future cash flows a company must generate given a discount rate.

Founders, and many investors, don’t appreciate that a valuation creates a burden of future performance, and the market is structured to set high demands of you.

Rule 4: Prices are set by the most optimistic incremental buyer.

Conventional wisdom suggests that markets set equity prices, but it’s the buyer willing to pay the most at any given time that sets the price. The rest of the market is irrelevant to establishing price other than to set a level at which the most optimistic buyer must exceed to be the highest bidder.

The most optimistic incremental buyer is both the one willing to pay the most for a company’s shares and demand the most in terms of future performance. Paradoxically, the more optimistic a buyer is, the higher a bar he sets for future demands on the company, lowering the odds that those future demands are exceeded. Lower odds are a natural and unavoidable outcome of greater demands.

As an operator, understanding valuation frameworks helps you balance the odds of succeeding against the demands that come from valuing your business vs. the tradeoff of minimizing dilution. And you don’t have to make it overly complicated to understand the demands that go into your valuation.

Rule 5: Keep it simple.

A common criticism of discounted cash flow models is that you can make them say anything by tweaking the assumptions, but that misses the point. The value of the DCF is in forcing yourself to define the assumptions. You can achieve a lot of the value of a full DCF by applying a simple multiple to future free cash flow (FCF).

Setting a multiple on future FCF requires defining four critical valuation assumptions:

- Revenue growth – how fast the company will grow and for how long.

- Margin trajectory – how profitable the company gets.

- Durability – how long the company will reliably generate cash.

- Required rate of return — the investor’s expectations for return on the investment, e.g. your cost of capital as an operator.

With these assumptions, you can estimate FCF at some point in the future as revenue x margin. Look out three to four years for that estimate. Then argue a reasonable multiple given market comps and relative durability. Your future FCF x your multiple is your future equity valuation. Finally, solve for your present equity valuation by discounting your future equity valuation back to the present given the required rate of return.

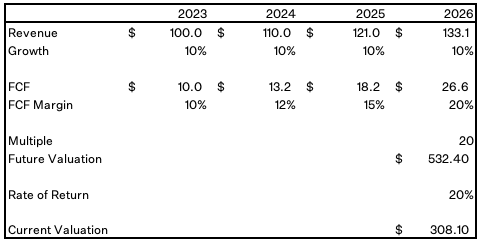

Take a simple example “Company A” raising money at the beginning of 2023. The company expects to grow revenue each year through 2026 by 10% and expand free cash flow margins from 10% to 20%. This means end period free cash flow in the model is $26.6 million. Comparable companies trade at 20x forward FCF, and Company A has similar durability and defensibility, so it assumes the same 20x FCF multiple. Assume your investors expect a 20% rate of return over a three-year holding period through the end of 2025, at which point your company will trade on 2026 estimates.

These assumptions yield a future valuation of $532 million at the end of 2025 discounted back to a current valuation of $308 million at the beginning of 2023.

While revenue and margins may be obvious to estimate, durability and rate of return may not. Those are more art than science.

Durability can be thought of as a combination of the strength of a company’s competitive moat and the persistence of customer demand. Companies with strong durability get high free cash flow multiples. Apple, Microsoft, Coca-Cola, and Costco trade at high multiples because of strong durability. Companies that have less perceived durability trade at lower multiples.

As for rate of return, equity isn’t free. It’s the most expensive form of financing, even though there are no contractually demanded payouts to equity holders like there are for debt holders. Investors in well-established companies often require lower returns than investors in riskier ventures. For private equity, the illiquidity of the investment is an incremental risk where investors often demand an “illiquidity premium” which means a higher rate of return.

Rule 6: Take Advantage of High Prices, But Understand What You’re Signing Up For

Markets go in cycles from boom to bust. It’s a natural part of capitalism. Conventional wisdom suggests that smart founders raise money when its cheap, which is true as long as you’re comfortable with the implications of raising at boom valuations.

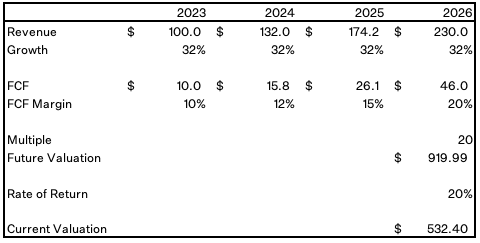

Take our prior example. Instead of a normal market, we’re in a boom time. The company that we reasonably calculated would be worth ~$530 million in three years and should be valued at ~$310 million today for a 20% rate of return can now get the full $530 million valuation today.

You can think about that in a couple of ways relative to our model. If our initial assumptions around revenue growth, cash flow margins, and future multiple were accurate, then the investor that pays $530 million for Company A today will have equity in a company worth $530 million in three years (assuming no further dilution, etc.) That’s a 0% compounded return. That’s a disappointment, which is what investors who underwrite boom prices are bound to receive.

The other way you can think about boom valuations is that they come with greater demands on the company if the company wants to continue to earn higher equity valuations. For Company A to still return 20% annually over three years, it would have to grow 32% compounded over the next four years with the same margin and multiple instead of the 10% compounded growth in our initial example. Or the company would have to grow 16% a year and trade at 30x FCF instead of 20x.

Either way, you need to deliver a brighter future the bigger the valuation, and eventually your valuation will match up with the fundamentals.

While it is smart net-net to raise money when it’s cheap, understand that this comes with expectations from investors and employees, who are also investors via stock grants. A rich valuation is not a free lunch. It’s an expensive lunch if you promise far more than you can reasonably achieve.

That’s all you need to know about valuation. Now go exceed the demands of whatever you raise.