At the Viva Tech conference in Paris, Google Chairman Eric Schmidt stated that he believes automation will create more jobs, not eliminate them. I think he’s wrong, and I hope he’s wrong. Disagreeing with the Chairman of the most advanced AI company in the world about automation is a dangerous game, but there are three things that can challenge his statement: timing, incentives, and economic realities. Let’s discuss his position through each of those lenses.

Timing. While Schmidt said he expects AI to create more jobs instead of eliminate them, it’s unclear what time frame he’s considering. When people talk about AI eliminating jobs, it’s almost always on how far out they’re looking into the future. Sometimes that’s five years, sometimes it’s 20, and sometimes it’s 50. At the same conference, GE CEO Jeff Immelt said the idea that robots would run factories in five years is “bullshit.” That I can agree with. The five-year picture of automation isn’t going to result in mass job loss, but the transition will start. Low-skill blue collar jobs will see continued automation. We should start to see autonomous vehicles and continued industrial automation.

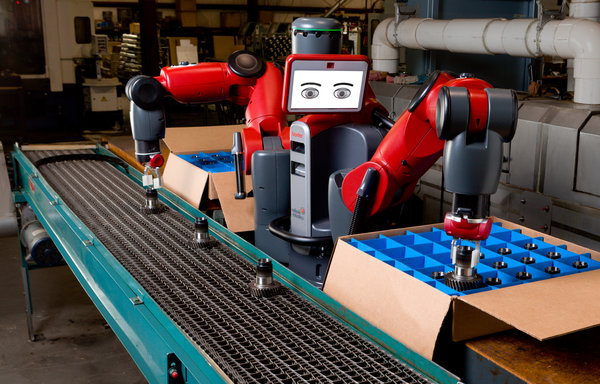

Long term, automation isn’t bullshit. If we don’t have machines and software capable of performing most of the tasks we call labor in 30, 40, 50 years, then it will be a failure of Google and our technology ecosystem. We already have machines that can see and hear. We have machines that can roughly manipulate objects in the real world. We have machines that can “understand” enough at a base level to be useful at specialized tasks. Robots don’t get tired, they don’t need breaks, and they don’t get distracted. They will eventually be able to do things with greater precision and sophistication than humans, whether physical work or knowledge work. When robots get sick (broken), they’re much easier to fix or even replace. Robots don’t need to commute to jobs, which saves on energy costs. Robots don’t need paid vacation or catered lunches. For all these reasons, robots will eventually be the most competitive option for the majority of jobs. A few more decades of improvement on artificial intelligence and robotics should yield far more capable machines that can perform almost all work more effectively and more efficiently than humans.

Incentives. Any discussion around job creation or loss is highly political, which means it’s also highly emotional. Many people get scared or even angry when confronted with the possibility of mass automation and human “unemployment”. Eric Schmidt is a savvy politician, and Google is the world’s leader in artificial intelligence development. He doesn’t want the world associating Google with job loss because it could negatively impact their business. He may also have other desires to serve in public office and is setting the stage for those ambitions. Either way, he’s incentivized to be an automation unemployment denier.

But the issue of incentives flows similarly to all executives and CEOs, Immelt included. They’re in an impossible political situation. If Immelt, or any CEO, were to embrace robots capable of eliminating human jobs, there would be backlash among their employees. No worker would be happy to be viewed as a stop gap to automation. There would also be massive PR backlash.

This psychological reality of having to avoid these negative incentives can have real impact on the progress of automation adoption. Decision makers who are caught between looking for improved productivity from automation and maintaining jobs may be forced to seek suboptimal solutions to keep humans employed. Over the past several decades, automation in factories hasn’t meaningfully improved productivity. One reason may be that robot installations approved by executives are done so with the goal of sustaining human jobs rather than maximizing total productivity.

Economic Realities. During his speech, Schmidt argued that not only could automation help create more jobs, but also raise wages. He said that if you “make people smarter” via computers, their wages should increase. In a vacuum this might be true, but in reality this seems to ignore supply and demand.

Let’s take an example in knowledge work automation. In the future, computers are going to be better accountants, financial advisors, actuaries, claims adjusters, etc. than humans. All of these are highly logical jobs driven by information. Per Schmidt’s argument, automating these functions should lead to more jobs, which may be true. Knowledge work jobs might still need a human front end to present the end results from the computer with a human touch (empathy); however, now you’re employing a good customer service operator, not an accountant. In fact, the human might not need to have much more than an entry level understanding of accounting and a positive demeanor to present the script that the computer provides them, which means that far more people are qualified to perform the job of presenting accounting results from a machine than are qualified to be an accountant. Given this great supply of potential workers, it’s hard to see how wages for workers replacing accountants would rival those of accountants today.

Knowledge work seems most sensitive to the economic realities of making humans smarter, but the same can apply to blue collar work. If autonomous trucking becomes a reality in the next decade, that might result in lower freight fees, which might result in increased demand for freight services, which might result in increased demand for dock workers or truck loaders; however, those skills are widely available and now there are a pool of unemployed truck drivers to fill those spots. Again, supply and demand would suggest businesses need not pay higher wages to attract workers to lower-skilled labor.

What We Can Agree On. Instead of debating whether automation will create jobs or eliminate them, we should instead start to set aside the modern dogma that humans must have jobs to survive and be productive. We should consider what a world would look like where humans don’t have to work. A world where all humans don’t need to worry about basic needs because of automation, freeing them to explore what it means to be human. Free to provide value through empathy, community, and creativity — the things robots cannot do. Maybe we won’t agree on the outcome of automation, but one point we hopefully all agree on is that the future is bright because of automation, not in spite of it.

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest: artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual reality, and augmented reality. From time to time, we will write about companies that are in our portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making investment decisions. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.