Human evolution depends on an ever-increasing rate of information creation and consumption. From communication to entertainment to education, the more information we create and consume, the stronger our society in total. Communication enhances community. Entertainment encourages creativity. Education builds knowledge. All of these elements build on top of one another like an upside-down pyramid, each new layer built a little bigger on top of the prior. It’s no coincidence that the Information Age of the last several decades has marked both the greatest period of increased information creation and consumption as well as, arguably, the greatest period of human progress.

The explosion of information created in the Information Age came with the tacit understanding that more information was good. The volume of information available to us is unprecedented, so the firehose is beneficial even if some (or perhaps much) of the water misses its target. The advancements of our technological devices that convey information have endeavored to bring the firehose closer and closer to us; from the non-portable PC, to the semi-portable laptop, to the nearly-omnipresent smartphone, to the emerging omnipresent wearable.

Now we’re continuously drowning in information.

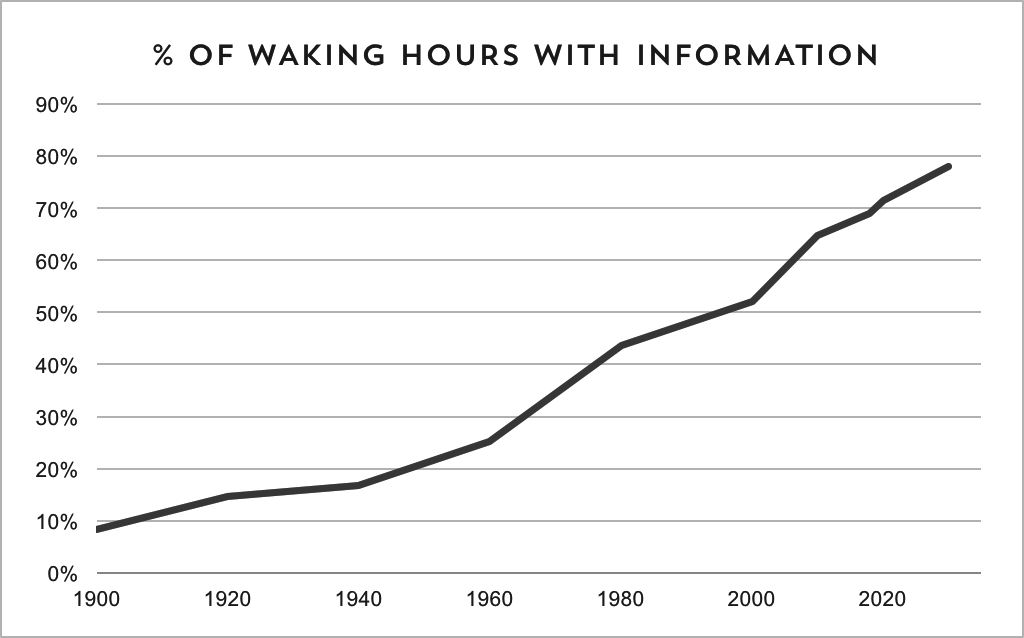

The average global consumer spends 82 hours per week consuming information. Assuming an average of seven hours of sleep per night, this means that 69% of our waking hours are engaged in consuming information. For many consumers in developed markets, that number is likely closer to 100%. It’s not often many people disconnect from information sources. Even when we’re not in front of a screen, the nearest one is always in our pocket, or there’s music or a podcast playing in the background. As a result, we consume almost 90x more information in terms of bits today than we did in 1940 and 4x more than we did less than twenty years ago.

Source: Carat, Deepwater Asset Management

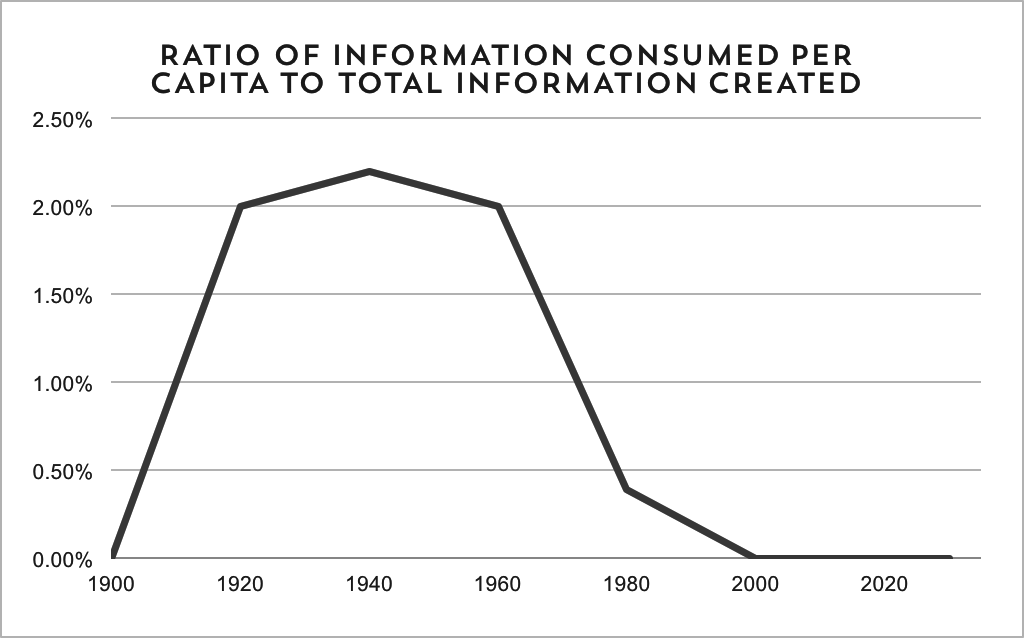

Not only are we maxing out time available to spend with information, we’re creating so much information that it’s impossible to keep up. The ratio of the amount of information consumed per year by the average person to the amount created per year in total is the lowest it’s ever been by our analysis. There’s always more information to consume, and the trend toward autonomous systems is only going to amplify that.

Source: Deepwater Asset Management

These two observations don’t paint a very positive picture of our relationship with information or our prospects for continued evolution, but in every challenge there’s an opportunity. We’re now preparing to exit the Information Age and enter two separate eras: The Automation Age and the Experiential Age. The Automation Age represents the natural continuation of the Information Age where artificially intelligent systems act on the vast amounts of information produced and quantity continues to dominate. The Experiential Age will define how the human relationship with information changes, creating new paradigms for communication, education, and entertainment. Out of evolutionary necessity, we will demand information with greater relevance, density, and usefulness than ever before. Meaning and efficiency, not quantity, will be the metrics on which we will measure information for human use over the next several decades.

Reintroducing Meaning + Information

Our current relationship with information is measured in quantity. Internet speeds are calculated in bits per second, as are hard drive speeds. Processor speeds are based on how many instructions they can perform per second, an instruction being a manipulation of bits. We even talk about how many messages we process a day, whether email, text, Snaps, etc. as a derivative of bits. We expect all of these quantitative measurements to improve over time, so we can consume more information faster.

One of the reasons we think about information in quantity is because of how information theory evolved. Claude Shannon developed information theory, built on work from Boole, Hartley, Wiener, and many others (upside down pyramid), to establish a method for accurately and efficiently transferring information in the form of a message from creator to receiver. His work on information theory yielded the bit and created the basis for modern computing. As Shannon developed his theory, he realized that the meaning of a message (the semantic problem) was irrelevant for establishing the efficient transfer of the characters that created the message, and therefore focused on the quantifiable aspects of the message instead.

It’s time to reintroduce meaning to information.

All meaning is established as a consumer’s interpretation of the creator’s intent (i.e. the creator’s version of meaning). The meaning of the same picture or movie or article may differ from person to person, even if the creator of the message might intend a single meaning. Since all interpreted meaning is some derivative of intended meaning, to contemplate “meaning”, you must contemplate both sides.

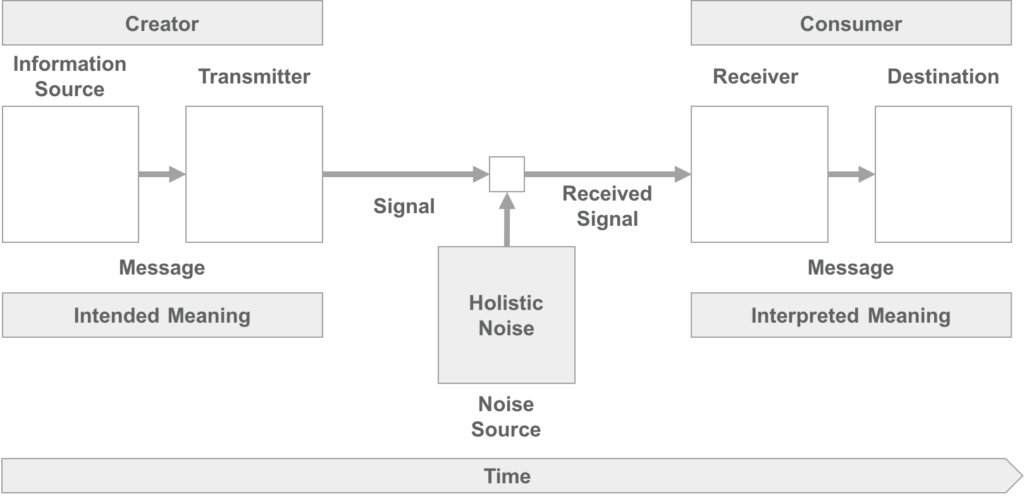

To help demonstrate the flow of meaning, it’s helpful to overlay the transfer of meaning on Shannon’s diagram from his groundbreaking piece on information theory:

The flow of meaning is analogous to the flow of information as diagrammed

by Shannon in “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”

A creator (human or machine) intends meaning in some message, which is conveyed to the consumer (human for our purposes) for interpretation via information transmission channels. A message is a container of information, which can be digital (e.g. a file) or physical (e.g. a book).

All intentionally transmitted messages must have some intended meaning, or the creator wouldn’t be able to conceive the message. Even a blank message is a reflection of the creator’s current mindset. Likewise, a message of random characters might imply boredom, or that a machine was programmed to do it, or it was a byproduct of some machine-learned behavior, etc. Messages transmitted by accident are free of this rule.

Since every message must be created with some initial meaning, all messages must therefore be interpreted because there is some underlying meaning to contemplate. A blank message might be interpreted as a mistake or a sign of trouble, a scrambled message might be a pocket dial, etc. This interpretation establishes the meaning from the message to the consumer.

In the process of transferring meaning, holistic noise impacts the interpretation of the intended meaning. It represents the natural disturbance between what a message creator intends and what the message consumer interprets. Holistic noise is created by differing contexts, that is, differing experiential, emotional, and physiological states between the creator and consumer.

Exploring meaning is a philosophical abyss — its precise characterization is engaging to discuss, but extremely hard to define. Nonetheless, the definition we’ve arrived at thus far is sufficient for establishing information utility, and further debate would distract us from the focus of defining utility.

Meaning/Time — The New Measure of Information

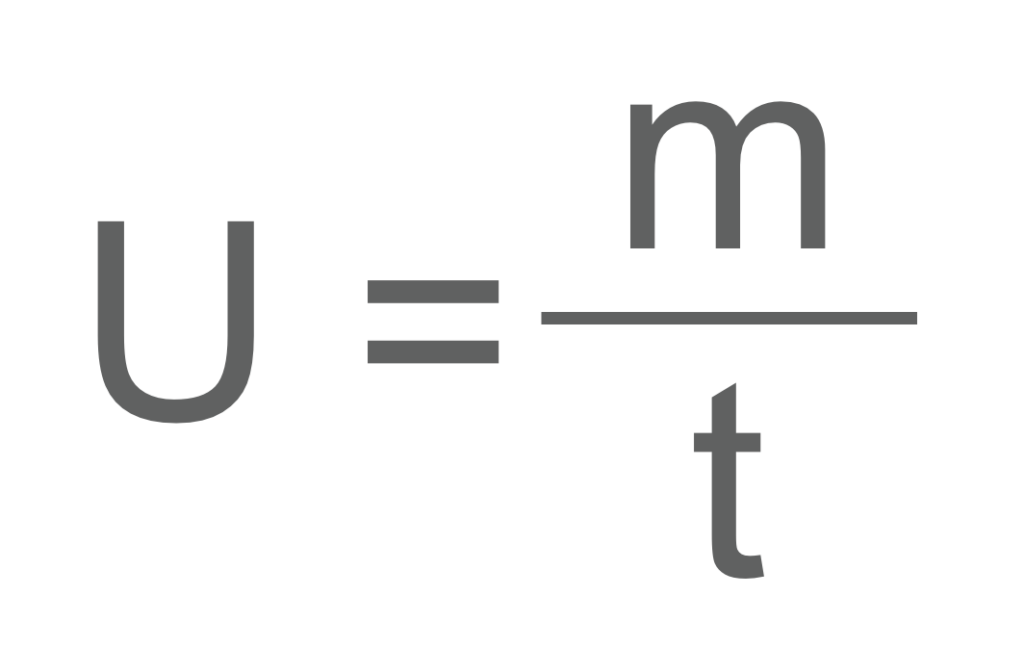

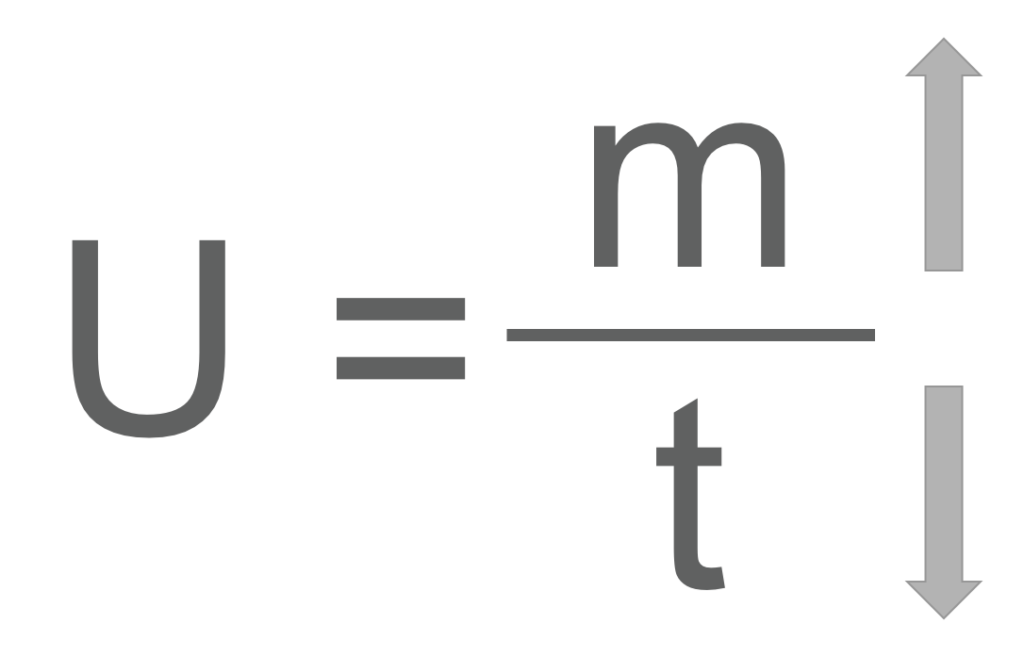

Thanks to Shannon, the quantity of information we can transfer is no longer a gating factor to the human consumption of information; the quantity we can process is. Therefore, the amount of meaning we derive from a message is now paramount, as is the time it takes to consume the message. To this end, we would propose that the value of a message in the Experiential Age should not be measured by bits in any way, but by meaning divided by time. We call this measure information utility:

Utility (U) of information is equal to the value of the meaning interpreted by the consumer of the information (m) divided by time it takes to consume the information (t).

Of course, meaning is abstract. How could you ever quantify it?

The closest we may be able to get is to borrow from marginal utility in economics. Just as we all have some innate scale with which we rank the value of consumer goods and that scale theoretically determines where we spend our money, we have a similar innate scale relative to the meaning of messages that should determine where we spend our time. We therefore measure meaning by time to help determine where best to spend our scarce asset of time just as we measure marginal utility by money to determine where best to spend our money.

Any individual’s scale for valuing meaning will likely be different, but that doesn’t matter. It only matters that we all have a scale that can consistently be used to compare the “meaningfulness” of the meaning we consume. In other words, we interpret the meaning of a message and then rank the perceived satisfaction or benefit we got from consuming it on an innate scale based on the aggregate of our prior experiences and expectations therefrom.

In reality, the scale is likely to be fuzzy (ordinal) rather than precise (cardinal). Most of us in any given moment wouldn’t be able to say message A is 11.7625% more meaningful than message B, but we would be able to say message A has more meaning than message B. That said, an information consumer can assign theoretical cardinal values to different messages based on the fuzzy scale, just as in marginal utility. Those cardinal values can be used to create a mathematical determination of information utility for the consumer.

Relevance and Compression: improving Information Utility

The next logical question is: How do we improve information utility?

The underlying intent of a message will always be the greatest factor in utility because all interpreted meaning (m) is a derivative of intent. A message of minimally useful or irrelevant intent will rarely be interpreted to have great meaning and thus usually have minimal utility. The answer may seem to be to improve the intent of the message; however, if you change the intent of a message, you change the message entirely, which is like telling the message creator to just say something else, ignoring their desire to convey their intended meaning.

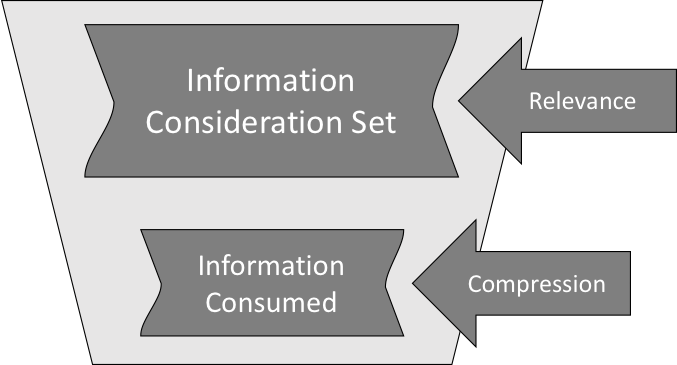

Improving information utility should not rely on changing the intent of a message and instead focus on matching a consumer’s need or want with a creator’s intent and then optimizing the conveyance of that intent. This leaves us with two core opportunities to improve utility: relevance and compression. Relevance ensures that a consumer is engaging with useful messages while compression enhances the presentation of a specific message to increase meaningfulness. To maintain our hose analogy: Relevance improves the hydrant that the firehose is attached to and compression distills the water itself.

One may argue that relevance is just another measure of meaning since by definition for some message have meaning, it must be relevant to the consumer. However, to argue that relevance is meaning assumes that it can only be applied post message consumption. The problem is that once a message has been consumed, its determined relevance (and by transference, meaning m) is immutable for that given point in time; utility cannot be changed after the fact. Therefore, leveraging relevance to improve utility must happen prior to the message consumption.

We define relevance as the reduction of the total pool of potential messages available for consumption (the consideration set) prior to consumption.

Relevance reduces the information consideration set, compression enhances the information itself

Today, relevance is optimized largely by data companies like Google or Facebook. These platforms reduce some large consideration set of messages that may be relevant to the user into something more focused to help reduce the user’s time seeking meaning. The more these systems know about our preferences, the more relevant information they can funnel to us. Of course, this creates a double-edged sword related to privacy, but all technology comes with tradeoffs. While it seems the data wars have been won by the information giants, the privacy wars have just begun. The hidden opportunity here may be for some platform to put privacy first and balance the careful line between keeping consumer data safe while still presenting the most relevant information.

Less time searching for relevant information means more meaning divided by time by avoiding less useful messages in the consideration set. The time saved can be spent consuming other relevant information, creating a greater aggregate value utility given time spent. Note that our version of relevance does not influence m/t for any specific message, only the set of messages considered; only compression can do that.

We define compression as a direct improvement to a given message that either enhances the meaning intended by the creator and/or decreases the time spent consuming it.

While the interpretation of the consumer is what ultimately establishes meaning for calculating utility, the compression of meaning depends on enhancing the intention of the creator and its consequent effect on the consumer’s interpretation. Compression doesn’t change the intent of a message, but makes it clearer and more useful, usually reducing holistic noise in the process. An example might be a set of written directions to a store vs a map. The underlying intent is the same, but the latter message should offer more utility provided the map is legible and accurate.

Historically, compression has happened via transitions to different information formats. With the advent of the written language, we went from the imprecise spoken word to the more precise written word. Writing a book or a letter is a form of compression relative to the spoken word because more thought and contemplation generally goes into writing vs discourse. Greater contemplation of the message should result in greater meaning of the message. More recently, the shift from written word to video is another example of relative compression. Video conveys relatively more meaning with less holistic noise than written words because the images help an information consumer see body language, emotion, and other factors that can be difficult to ascertain through words alone. This doesn’t mean that video is the perfect medium of transmission for every message — the written word can be effective for certain purposes — but there is relative compression when comparing writing as a message format vs video as a message format.

Compressing relatively more meaning into less time will be a prominent factor in the Experiential Age. If we can get more meaning in less time, we will spend more time with the technology that delivers that benefit. To that end, there are several emerging opportunities around compression:

Stacking Information Purposes. Content formats like GIFs and emoji combine communication and entertainment by replacing text. When a message creator picks a specific GIF or emoji to express themselves, it carries not only the underlying intended message, but an added element of emotion and entertainment. These added elements not only increase the meaning transferred, but also reduce the holistic noise between the message creator and consumer. Most obviously, when someone sends a GIF of a shaking fist or a coffin emoji, they probably aren’t seriously mad.

Platform-Enforced Time Restriction. While some content platforms are moving away from time restriction, like Instagram and Twitter, placing an artificial cap on the length of a message will always compress meaning. When an information creator is forced to deliver his or her message in limited time like a 140-character tweet or a six-second Vine (maybe now v2), it demands creativity and precision that results in greater meaning for the consumer. This incurs an additional cost of time to the creator to make their message succinct but still meaningful; however, the burden of quality in a message is always on the creator, and perhaps many messages aren’t worth the time to send in the first place.

Consumer-Enforced Time Restriction. In some cases, information consumers put the restrictions on time they’re willing to spend consuming a creator’s message. This is most apparent in the shift to digital assistants. When an assistant answers a consumer’s query, the consumer is not willing to listen to a painfully long list of ten possible answers. They expect one answer; the right answer. In this sense, the consumer shifts the burden of time he or she previously spent deciding the best answer from a set of options back to the creator that established the options in the first place (i.e. Google, Amazon, Apple, etc.). Relevance has always been important in the consumer Internet, but increasingly so here. Companies with extremely large customer datasets are the only ones able to play in this game because data allows the digital assistant companies to infer the context of the consumer and tailor messages appropriately.

Information Layering. The emergence of augmented reality (AR) has enabled the concept of information layering. Now a picture or video can be enhanced by stickers or lenses that add additional information related to the original purpose of the content, most commonly entertainment today. The layered information acts somewhat similarly to stacking information purposes in reducing holistic noise by adding context. As AR continues to evolve, the layered information can become more educational or instructional. For example, AR can compress knowledge about how to do something from a book or 2D video that suffered from the friction of transferring that meaning to the real world, to overlaying that meaning on the real world itself; another example of reducing the holistic noise between creator and consumer and improving meaning in time.

Scarcity. By limiting the number of times someone can send a message or components of a message, content platforms can create artificial scarcity similar to a time restriction. In this case, the restriction applies to the meaning side of the equation. If a message creator chooses to leverage a limited resource in a message (other than time), it should confer greater meaning to the consumer because it comes at an opportunity cost to the creator. An example might be some of the frameworks emerging around the ownership of unique digital goods, which could extend into transference of meaning through those goods. When a creator includes a one-of-a-kind component to a message, the intended meaning increases, which should also increase interpreted meaning.

Time Manipulation. Since the majority of content we consume is digital, much of it can be sped up or slowed down according to the consumer’s preference (i.e. videos, audiobooks, podcasts, etc.). Time manipulation requires no additional effort on the side of the creator; it only requires the consumption tool to enable it. While time manipulation techniques are effective on an individual level, they’re less interesting than the other opportunities because they’re optional to the consumer where the others are common across all consumers.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI). The development of brain-computer interfaces will, in theory, create a direct way to receive information from and transmit information to the brain. A deeper understanding of how we create meaning from a neurological perspective is embedded in this future, thus BCI should reduce holistic noise and enhance meaning. An example may be that a message transmission mechanism could understand the contextual state of both the message creator and consumer and alter the message as appropriate in an effort to match states. While BCI is exciting technology, it has a long clinical path that is just beginning before we can consider using it for meaningful augmentation.

It bears repeating the message creator’s intent is paramount to utility. A useless message is still useless no matter how you dress it up. However, a more compressed version of a given message should always be more useful than a less compressed one given the same baseline intent, so we should strive to compress messages as much as possible.

The current opportunities in compressing information should be relevant for the next 5-10 years or more, particularly in the case of BCI. That said, the aforementioned concepts and technologies compress information relative to how we consume it today. As they become the standard for future information transmission, the bar must move correspondingly higher, and we will need to find new ways to compress information even more. Therefore, while the human desire for increasing information utility is eternally valid, how we compress more meaning into less time must always evolve.

Embracing Information Utility

It’s popular to lament our overexposure to information, ever-shortening attention spans, and superficiality of what we create and consume, but technology has always been a Pandora’s Box. Now that we’ve gone down the path of near-constant connectivity, it’s impossible to walk it back. While it can be beneficial to spend less time with information when possible, we have to embrace the path we’ve created; embrace the unending flow of information. Discovering ways to leverage new content formats and technologies in ways to transmit useful information is our future. Demanding more meaning from that information we choose to spend time with is the next evolutionary step for humanity.

Improvements in relevance will continue to be driven by technology, but as we think about the opportunities in compression, it’s clear that utility will not be driven purely by hardcore technologists, but also by hardcore creatives. Injecting more creativity into how we convey meaning, something that is unique to the human experience, make up some of the biggest opportunities in improving information utility. After all, the humans that consume information determine the utility of it, not robots.

Some people fear the coming Automation Age will devalue humanity, removing purpose and meaning from our lives. Luckily, we have this survival instinct — this innate need for more information, more knowledge. That curiosity means there will always be a purpose for us. As automation frees us from the constraints of labor, the Experiential Age will bring about a golden era of exploring what it means to be human, and information utility will guide the way.

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we will write about companies that are in our portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making investment decisions. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.