Neurotech for Feedback

In Volume I of this series on Consumer Neurotech, we established a framework for thinking about Consumer Neurotechnologies and their value propositions. In Volume II, we discussed neurotechnologies that have the value proposition of Control (or, using our taxonomy from Volume I, neurotechnologies whose “Effect-type” is Control). In this third Volume, we’ll learn about and analyze neurotech that leverages a phenomenon known as “neurofeedback.” Neurofeedback is a straightforward idea: record some aspect of neural activity, and feed that activity back to the brain through one of the senses. By doing so, the neurofeedback can help a user achieve a desired brain state.

Neurofeedback for Attention

Fiction

This morning, walking into the espresso bar en route to work, you ran into a friend you hadn’t seen in months. When you’d seen her last, she told you she thought her boyfriend might propose soon. This morning, you updated her on your project at work, your son’s first words, and other little things, but you could tell she was waiting. Finally, you had yielded the microphone and she promptly broke the news by holding up her hand. When you saw a glistening engagement ring, you felt a rare, precious vicarious excitement. You were chatting away excitedly but realized if you stayed any longer you’d be late, so you hurried over to the office riding the high on life. You’ve finally just now squeaked into your swivel chair, and your priorities are evident: text friends about the engagement first, second, third…get work done later. The adult in you tries to wrestle control back, and you start listening to music through your headphones. When you first put them on, they’re constantly dinging, telling you that you’re unfocused. The dings work like chimes in wind, catching your attention and slowly zoning you into trance-like productivity. 15 minutes later, you’re in flow, and there’s a small smile from this morning still cemented onto your face.

• • •

One well-known application of EEG is for assessing focus and attention: certain patterns in EEG signals indicate greater or lesser degrees of attention. Given the volume of research, patents, and practical utility of attention enhancement, we’re likely to see an abundance of products that leverage these signals. Here, we’ll discuss two such products on the market.

Mindset

- Medium of innovation: Integrated

- Device-type: Record

- Form-factor: Headphones

- Effect-type: Feedback

Mindset is a pair of headphones that integrates EEG sensors into the headband. The goal of the $280 headphones is, as per their website, “[With] our powerful EEG technology, you will train your subconscious to recognize and tune out the things that distract you.” According to Mindset’s explanation of the science behind their product, they use the principle of neurofeedback to provide an auditory cue through the headphones whenever a user loses focus. Through this feedback, over time, the user’s brain will become trained to stay more focused. Mindset is launching in the coming months; preorders are active on their website.

NeuroPlus

- Medium of innovation: Integrated

- Device-type: Record

- Form-factor: General Headset

- Effect-type: Feedback

NeuroPlus is a $100 EEG device that’s paired with attention-enhancing games. Like Mindset, NeuroPlus leverages neurofeedback: “[Users] play brain-controlled video games that give real-time feedback on how well they’re paying attention. The more they focus, the better they’ll do in a variety of fun, interactive training games. Over time, this practice leads to improved focus in everyday life.” Users are granted access to the games for $30 / mo. for an individual, $50 / mo. for a group of 2-4 people, and each additional person beyond the fourth adds $10 / mo. to the subscription price. A large part of NeuroPlus’s target market appears to be children with ADHD, and they include a 60-day money-back guarantee so that users can have a fair shot at determining whether the device and software work for them.

Takeaways

- Mindset and NeuroPlus both integrate attention training into pre-existing use-cases: for Mindset, it’s music-listening; for NeuroPlus, it’s gaming. This is a theme in consumer neurotech: it’s useful to find pre-existing contexts in which to use the technologies. To show how this makes sense, suppose we’re comparing Mindset with Thync (a device we’ll discuss in Volume IV that attaches to the user’s temple and stimulates nerves—the goal is to help a user relax or feel energized, i.e. to modulate their affect). Mindset benefits because users have already developed behaviors for using headphones and opening up an application (e.g. Spotify) when they want to wear their headphones. In contrast, Thync requires the new behavior of placing adhesive strips on the device, then putting the device itself onto their forehead with no purpose other than to modulate affect; this is a high-friction requirement. We suspect that not only will it lower friction to deliver neurotech value through pre-existing use-cases, but it will also make prospective users more comfortable with the idea of technology that records or stimulates neural signals—comfort is born of familiarity.

- The fact that neurotechnology can be packaged into existing use-cases will be a boon to its uptake. Contrasting with mixed and virtual reality, neurotechnology doesn’t need a “killer use-case” because it will piggyback on use-cases that are already killer, such as listening to music.

- Mindset takes advantage of the fact that they can place EEG sensors into hardware that people are already used to using (Halo Neuroscience does something similar, although Halo’s headphones are less ergonomic and some athletes don’t wear massive over-ear headphones while working out, perhaps to avoid pooled sweat). NeuroPlus, in contrast, requires a dedicated but low-profile EEG headband.

- It’s interesting that the actual usage of neurotechnology generally recedes into the background: neurotechnology isn’t necessarily the primary experience a user is aware of when interacting with a product. This is true of the CTRL-kit, the Muse (see below), the Halo headphones, the Mindset headphones, the NeuroPlus games, and more. Consider that even the semantics of “augment” or “enhance” make this evident: we have to augment something, enhance something. These verbs need their nouns.

Use-Cases and Market Size

We’ve split the market size here into two categories: attention training for people with ADHD (like NeuroPlus), and attention training for inducing flow state (like Mindset).

ADHD

For a given year, we can estimate this market size by combining a total addressable market scaled for market penetration with the price of the hardware and annualized cost of a subscription. 6.7M children in the United States have been diagnosed with ADHD, so we use this as the TAM in our calculations. We use NeuroPlus’s price point of $100 for the hardware, and a 12 x $30 / mo. = $360 annual subscription cost. We estimate that in 2025, the American market for ADHD-targeted attention training will be $113,000,000. In 2003, there was over $2B of U.S. spending on ADHD medication, so the ceiling on this market is high.

Flow

Given the ubiquity of using headphones to help focus, we assume for this calculation that headphones will be the most common form-factor for focus enhancement. As such, our starting point is that the smart headphone market is expected to be $0.995B in 2018 and $2.825B by 2022. In 2016, Bose had 8% of wireless headphone sales. We’ll assume that this market share stays constant. A pair of Bose QC35 headphones cost $350, so using the 2018 figure from above, we can estimate that Bose sold roughly 227,430 headphones in 2018. In 2022, that would mean 645,700 headsets sold assuming constant market share. With linear growth, this would grow to 960,700 Bose headphone sales in 2025. We assume the size of the Bose market represents the upper bound for the total number of headphones that will incorporate neurofeedback features by 2025 (including and in addition to Mindset). We use an exponential curve to model the growth of neurofeedback headphone sales from 2018 (estimated at 5,000) to 2025 (estimated at the upper bound of 960,700). Using this as our model, we estimate that in 2025 there will be $269,000,000 in neurofeedback headphones sold for the purpose of more easily entering flow and staying focused during productivity sessions.

Neurofeedback for Meditation

Fiction

Every morning, you wake up and tell yourself with stern-voiced and earnest conviction that when you come home this evening, you’ll write another page of the short story whose idea was seeded months ago by a chance interaction on the street. Every night, you come back from work carrying a boulder’s weight of tension in your shoulders, and the creative in you sits cowering in his corner, terrified of the stress and refusing to be coaxed out. Tonight is no different: you walk in the door, take your backpack off, sling it around and let it slam down on the floor. Every morning, your glance at your laptop is loving and longing, wishing for the chance to sit down and have a conversation with a blank screen, mediated by keys. Every night, with this one as no exception, your eyes seem to have the same magnetic polarity as your computer: by a mysterious cognitive law of physics, you can’t bring yourself to look at it. The only escape from this internal battle is to sit down on your couch. You close your eyes, wishing that energy and motivation would return to bring you back to your early-morning fervor. Didn’t you hear on a podcast that meditation can help clear the head after a long day? Wait—you still haven’t opened that meditation headband your mom curiously gifted you for your birthday three months ago. You dig it out from under accumulated magazines and daily material acquisitions and follow the instructions for set-up. A little while later, after fumbling around through the on-boarding in your tired state, you thank yourself for purchasing such a well-crafted comforter as you lay back with the headset on and the app open, ready to give it a try. Thirty minutes later you emerge and feel strangely refreshed. Tonight, you decide, you’ll sleep—but tomorrow, you have a new approach to tackle that tension and maybe, just maybe, you’ll wind up in an invigorating tango with a word processor, bringing that street-encounter to literary life.

• • •

In a similar vein to its application to attention, EEG-based neurofeedback paradigms can be applied to meditation as well.

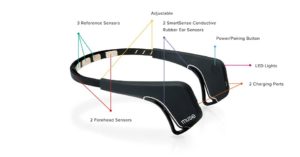

Muse

- Medium of innovation: Integrated

- Device-type: Record

- Form-factor: General Headset

- Effect-type: Feedback

The major player in this space right now is Muse, built by InterAxon. The Muse is a $200 headband with EEG sensors and comes with a companion app to help users meditate more effectively. The app delivers sound to a user through their headphones and uses the real-time EEG signal to determine whether or not a user is in a meditative state. The app will change the sounds based on the EEG signal. Muse offers the Muse PRO software to professional therapists and meditation guides for ~$35 / mo. With the subscription comes access to Muse Connect, a SaaS platform for using Muse to assist with a professional practice. This subscription also includes a reduced price for practitioners’ clients who purchase the headset as part of a referral program, in addition to access to case studies, best practices, and more. Muse also has a developer program where developers can gain access to raw EEG data from the headset in order to use it for their own applications or for research.

Takeaways

- One of our team-members tried the Muse a couple years ago, and they were neutral-to-negative on the experience of the neurofeedback. Two important caveats are that a) the Muse and its software have likely improved since then, and b) our team-member had no guidance (and therefore lower motivation to keep trying). This latter point may, hypothetically, explain why Muse is marketing the device heavily through meditation guides and therapists: they might be finding that individual users aren’t using the product properly/consistently.

- This insight is applicable to consumer neurofeedback as a whole: neurofeedback inherently takes time to work, and this means that users will have to use the products for a while sans value add (note the similarity to the exercise, dieting, and broader meditation industries). That’s a big ask to make of a user, and Muse’s way around this is to use another human—the professional meditation guide or therapist—as a forcing function. NeuroPlus takes a similar approach with the parents of children with ADHD. This contrasts with Mindset, whose product inherently adds instantaneous value by playing music, regardless of whether the neurofeedback actually works. While Mindset will only succeed in the long-run if the neurofeedback succeeds, the inherent value should make it easier for users to try out Mindset for a sufficiently long period to see improvements.

- Control devices like CTRL-kit or various Commoditized EEG applications have immediate value.

- The meditation and self-care markets are rapidly growing (more on this below), so this could be a promising opportunity area in the sense that people are actually taking the time to use meditation apps like Headspace and Calm, which require repeated usage to work. What are the success factors for these apps? How much effort do they require of the user? Why are users coming back? How long does it take for users to perceive the value-add? Perhaps the answers to these questions will be informative for neurofeedback products.

- Neurofeedback products contrast with neuromodulation products like Nervana and Thync (to be discussed in Volume IV), which are “on/off” in that the user just has to turn them on in order to receive value from the product, whereas neurofeedback products take time. It’s important to consider the psychological impact of on/off technologies. A 2017 paper by Weible et al. reported on an experiment where meditation-like brain states were switched on and off in mice using a neural interface. When these brain states were on, the mice showed behavior consistent with reduced anxiety. Extrapolating into the far future, neurotechnology could conceivably turn many things we currently have to work for into “on/off” experiences; we think it’s important to begin investigating the psychological and cultural impacts this shift might cause.

Use-Cases and Market Size

We tailored this projection to Muse’s current business model of selling both direct-to-consumer and through professional meditation guides and therapists. There are 2450 meditation studios/centers in the U.S., and we estimate three professionals per studio. The number of behavioral therapy practitioners is ~100,000. Summed, these give us an estimate for the number of professionals who might purchase subscriptions to Muse PRO.

There are conflicting reports on the size of the meditation market: according to one source, 18M adults in the US (8%) meditated in 2012. According to another, only 9.3M adults (3.7% based on 2017 population) in the US meditated during the year-long period covering parts of 2016-2017. We’ll take the conservative approach and use 9.3M as our estimate for the number of meditators in the US right now (if the number of children and teenagers who meditate is non-trivial, then this is certainly an underestimate).

In 2017, there were 1000+ meditation apps available, which conjointly with websites and online courses generated $100M+ in revenue. The total meditation market was $1.21B in 2017, and is expected to have 11.4% average annual growth to $2.08B by 2022. There seems to be big growth in meditation app uptake. Calm had MAU that grew 81% YoY in 2017-2018; self-care app installs are up 36% YoY, and consumer spending in the top 10 self-care apps was up by 40% YoY.

To calculate how many digital meditation app users there are, we divide the market value for apps by the total market value: $100M / $1.21B = ~8.3%. This is probably an overestimate, since many meditators don’t pay for meditation. Therefore, if we’re going to use this as a proxy for figuring out the number of meditators, we need to scale the denominator accordingly. We estimate that the number of paying meditators is only 25% the number of total meditators, so we divide 8.3% by 4 to estimate that 2% of total meditation users use digital meditation apps. Finally, multiplying the 9.3M meditators of 2016-2017 by 2%, we arrive at 186,000 digital meditators in 2017 (since our math is loose, we’re comfortable removing the ambiguity of “2016-2017” from our estimate).

As described above, digital meditation is growing very quickly; hence, we’ll assume a 20% YoY growth sustained through 2025. All told, we calculate there will be ~666,500 digital meditators in 2025, which seems a sane estimate (only 7% of the 9.3M adult meditators in 2016-2017).

Finally, we scale this by market penetration and account for Muse’s business model to yield our final estimate of a $30,280,000 market in 2025.

Neurofeedback for Sleep

Fiction

You read about empathy often these days, and normally you think you’re fairly decent at it. You frequently imagine yourself as your waiter when you dine out with your colleagues, and act in a way you think will make the interaction meaningful and invigorating. You read competing views on political topics and feel torn by testimonials at odds with each other. Your empathy has a hard limit, though: those so-called “morning people” are full of it. Mornings are Atlassian at best, Sisyphusian at worst. You’re a different person for those 45 post-wakeup minutes than for the rest of the day. Your eyelids experience gravity more strongly than anything else, and your soul feels destined for the underworld. Mornings are, unequivocally, the worst. Two kind and clever colleagues of yours became tired of your morning mood and pitched in to purchase a headband that supposedly helps improve your sleep and your wake-up experience. That was two weeks ago. No, maybe three? Hold on a second…you’ve only been awake for five minute and you’ve been thinking about all of this—that never used to happen! Coherent thoughts at this hour? Unheard-of. You roll out of bed lithely (unprecedented) and open up your phone, checking your sleep stats. The graph is moving slightly, but definitively, upwards. Well, you think, I suppose I have an extra 30 minutes to kill, now. You glance over at the waist-high stack of books in the room’s corner. Might as well…

• • •

Sleep problems are ubiquitous, and as with attention and meditation, the underlying troubled system is the brain. Therefore, sleep is a prime candidate for neurofeedback using EEG and other biosignals.

Dreem

- Medium of innovation: Integrated

- Device-type: Record

- Form-factor: General Headset

- Effect-type: Feedback, User Characterization

Dreem, one of the leading companies using neurotech to improve sleep, estimates that across Europe and the U.S., 1/3 of the adult population has poor sleep quality. Dreem is a $500 headband that contains EEG sensors, an accelerometer, and a pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygenation. With these biosignals, Dreem uses algorithms and a companion app to add four types of value to users who wear the headband while they sleep: they fall asleep faster, get deeper sleep, wake up more refreshed, and can analyze their sleep over time and therefore improve it. Users wear the headband at night and can check their sleep stats in the morning on their phone.

Takeaways

- Among Dreem’s four discrete value propositions, three require no effort from the user: 1) to fall asleep faster, the headset provides audio cues. 2) Similarly, audio is used to facilitate deep sleep. 3) Dreem induces a gentle wake-up by playing the user’s alarm at different times depending on their sleep stage. Achieving the 4th value proposition of long-term sleep improvement, however, requires the user to consistently check in with the sleep data collected by the headset, and compare this to their lifestyle; ultimately, if a user wants to benefit from this information, they have to enact changes in lifestyle themselves. This duality of value proposition—effortless and effortful—probably works to Dreem’s advantage since even for users who don’t put in the effort, the device can still be useful.

- 7/60 reviews on TrustPilot complained about the comfort of the Dreem device. Discomfort will reduce the addressable market for Dreem and any other head-worn consumer neurotech.

- The Dreem companion app features a Sleep Score that characterizes how well a user slept. Referring to this score, one testimonial from their website reads, “It’s very addictive! It’s very interesting to see the scores of the night.” Quantitative self-improvement can become addictive—what are the ethics around using biosignals as the quantitative value that causes addictive usage behavior, as opposed to external signals like a score in a video game?

- Dreem offers a high-quality white paper about the science behind their product. The paper contains information about how the biosignals are processed, where and how Dreem uses algorithms, and the efficacy results. In our view, this ought to be the gold standard for articulating the science behind a neurotechnology product. It has ethical value, and it’s also a smart business decision: customers will be more comfortable using the product, investors will be more comfortable investing, and influencers will be more comfortable influencing.

Use-Cases and Market Size

The total addressable market for sleep products is large: in the United States, 131M people have sleep problems. This TAM should be scaled back by a factor representing the proportion of people who can sleep comfortably with a head-worn device. To do this, we use the fact that 7/60 reviews on TrustPilot mentioned discomfort. We round this up to 10/60 to make the clean estimate that 1/6 people will find the headset too uncomfortable to sleep with. This would shrink the TAM to 109.2M people.

We estimated market penetration ad-hoc based on our sense of what’s reasonable. We suppose that 10,000 Dreem units are sold in 2018, and 1,000,000 units are sold in 2025. We also assume the ASP of this product will decrease over time from $500 to $200. Our estimate for Dreem’s wearable sleep enhancement market in 2025 is $200M. Assuming that other companies come along with unique hardware and software innovations, Dreem’s market will be only a subset of the total size of the neurotechnology-enhanced sleep market.

Conclusion

In Volume III of our five-part series on Consumer Neurotechnology, we took a look at neurotech that leverages neurofeedback to drive value to users. In Volume IV, we’ll explore consumer technologies that directly modulate the human nervous system. Stay tuned!

- Volume I: Introduction

- Volume II: Neurotech for Control

- Volume III: Neurotech for Feedback

- Volume IV: Neurotech for Brain Modulation

- Volume V: Other Neurotech (The Odd Ones Out)

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest or may invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we may write about companies that are in our portfolio. As managers of the portfolio, we may earn carried interest, management fees or other compensation from such portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making any investment decisions and provided solely for informational purposes. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections and the content on this site should not be relied upon. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.