This piece was initially published on Doug’s blog, Contrarian Mindset.

Capital allocation is the most important job of every CEO, from startup to public company. This is contrary to the belief that being a good operator is the most important thing.

Capital allocation is “the process of deciding how to deploy the firm’s resources to earn the best possible return for shareholders.” If you invest in the wrong things, your returns are capped no matter how well you operate the functions around which you invest.

Good capital allocation finds the best uses of company resources to set the organization’s return ceiling. Operations allow that ceiling to be met.

There are few truly great capital allocator CEOs because most focus on operations. Operations are a daily requirement and easily measured. When things go wrong in a business, it’s usually related to operational issues that are readily apparent. By contrast, capital allocation decisions seem infrequent and abstract. The effects of those decisions may not be obvious until some date in the distant future.

While the capital allocation topic has grown in popularity with public companies, it’s largely ignored by startups and growth companies. This is a mistake. Thoughtful capital allocation is just as important, if not more, at a company’s earliest stages. It sets the groundwork for a company’s future success in generating shareholder return. Poor early capital allocation policies create a sort of technical debt that will haunt the company in the future.

This guide offers a framework for startup and growth company CEOs to think about capital allocation for their organizations in four pieces:

- The capital allocation lifecycle from startup to mature company

- Why capital allocation is important

- The menu of capital allocation options by life stage

- Rules for capital allocation by life stage

This is not a guide to calculating ROIC or other capital return metrics. There are other great guides to that financial exercise. Calculating ROIC is a useful pre- and post-mortem tool, but as with so many decisions that involve uncertainty, the qualitative aspects matter more than the quantitative.

The Capital Allocation Lifecycle

There are three distinct capital allocation phases for any given company:

- Startup

- Growth

- Mature

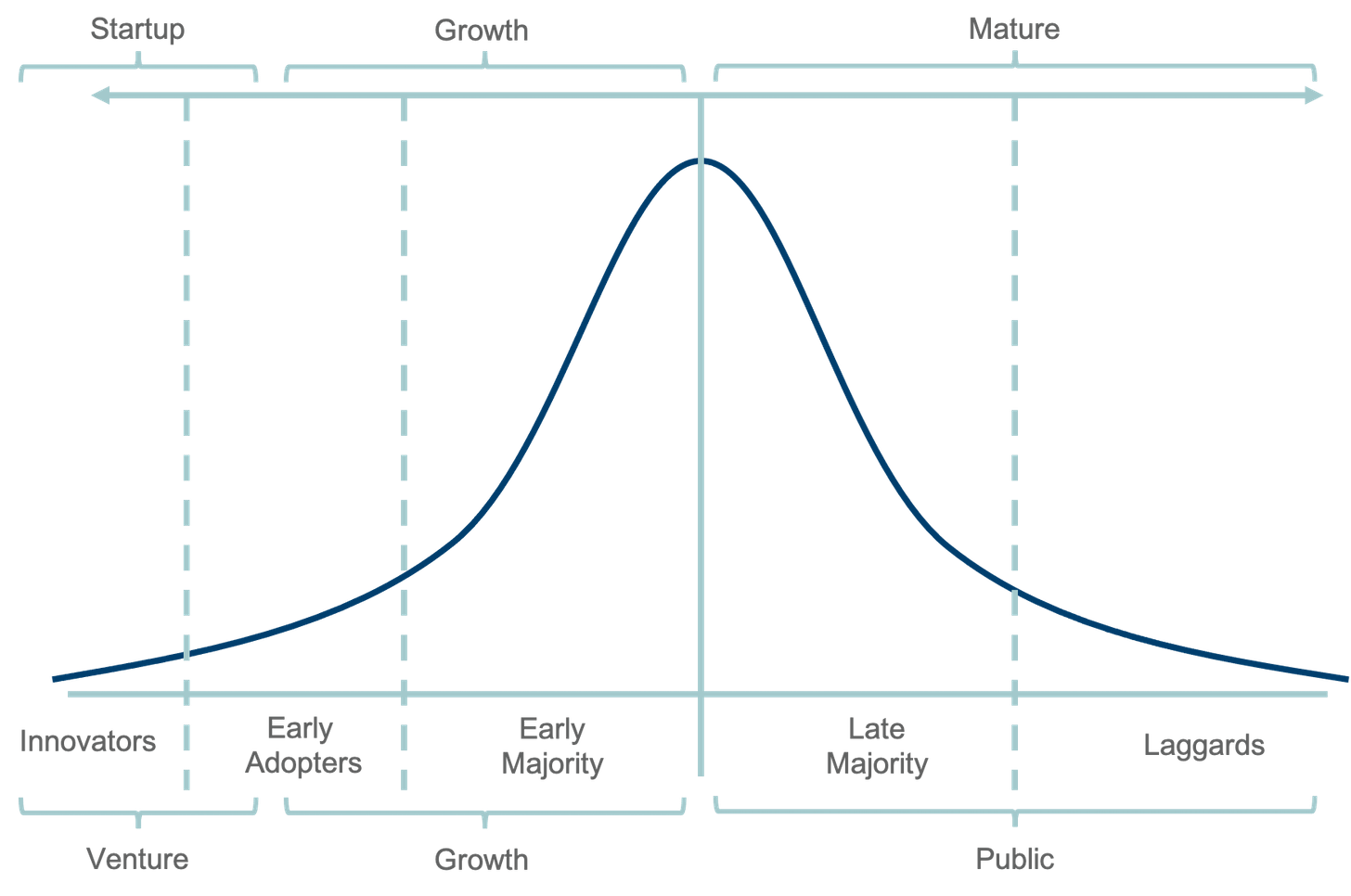

The three phases of capital allocation roughly track both the technology adoption life cycle and equity capital market definitions of venture, growth, and public.

Each phase comes with a different basic mandate for capital allocated to the company by shareholders. Startups are expected to find some sign of escape velocity as defined by customer adoption. Growth companies are expected to achieve market capture. Mature companies are expected to generate superior relative shareholder returns.

In the long run, shareholder returns will roughly track what the underlying business earns on its capital. To quote Charlie Munger:

“Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return that the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six percent on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you’re not going to make much different than a six percent return – even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen percent on capital over twenty or thirty years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.”

That’s why everyone wants to own Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook. They all generate strong returns on invested capital and will likely continue to do so for a long time. If a CEO’s goal is to create a large, world-defining company, or even just a decently successful one, the CEO cannot escape the mandate of thoughtful capital allocation.

The Capital Allocation Menu

In The Outsiders, William Thorndike describes five ways that managers can allocate capital as “investing in existing operations, acquiring other businesses, issuing dividends, paying down debt, or repurchasing stock.”

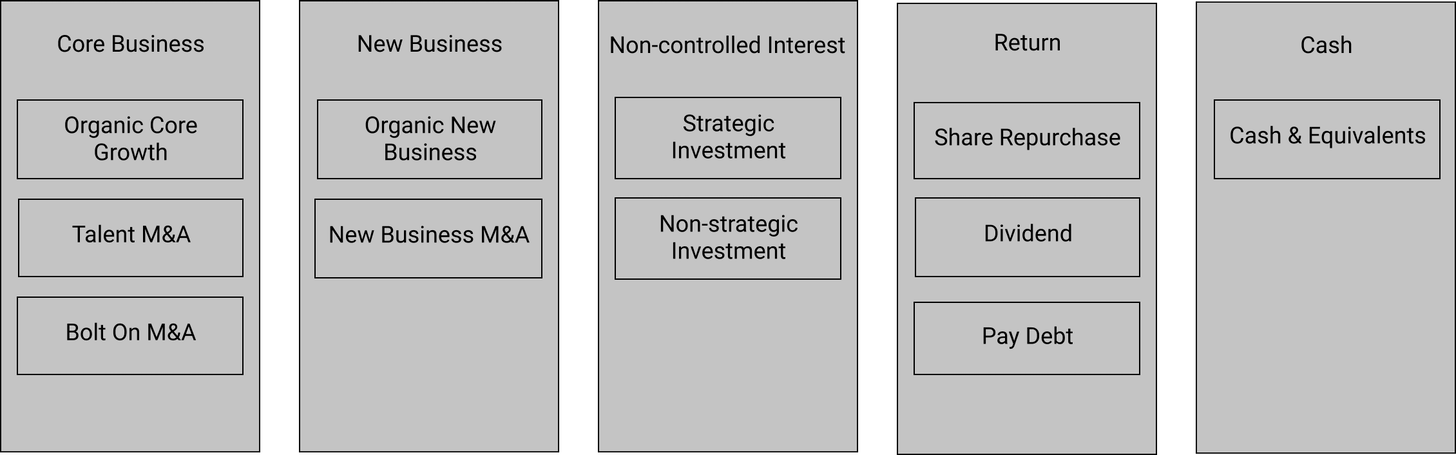

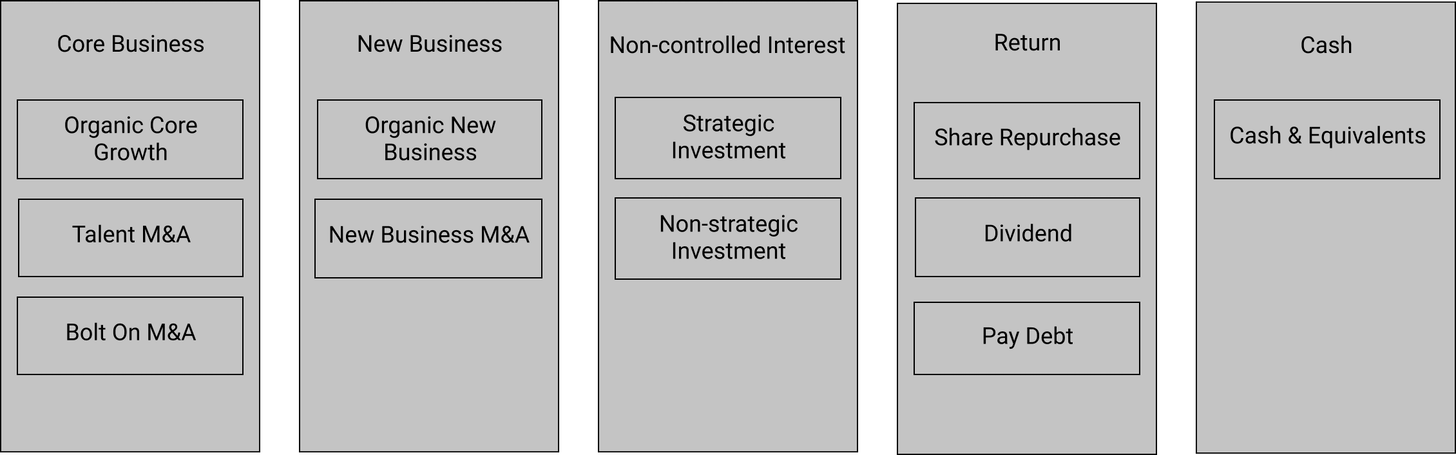

From studying the FAAMG companies over the past decade, I view the options to capital allocators in five slightly different buckets:

- Core business

- New business

- Non-controlled interest

- Return

- Cash

Each of the five main capital allocation categories have sub strategies that specify use of capital. In particular, this framework distinguishes between types of M&A and strategic investments that may not have been as common in the era of The Outsiders whose strategies were employed several decades ago.

To detail each of the sub strategies:

- Existing Operations: Organic Core Growth. This is often the first bucket that gets filled by allocators — investing in the needs of the core business. Investment here takes the form of research & development, sales & marketing, capital expenditures, and working capital.

- Existing Operations: Talent M&A. Not all M&A should be viewed at equally. Acquiring a business to continue operating is different than acquiring a team for talent that will be reallocated to the existing business. Talent M&A usually represents an alternative form of R&D investment.

- Existing Operations: Bolt On M&A. Whether to save time or because of lack of ability to build it, bolt on M&A extends a company’s existing offering through acquiring an external product or service. Examples: John Malone’s acquisitions of other cable companies to expand TCI’s coverage, Apple buying Beats to accelerate the creation of a subscription music offering alongside iTunes.

- New Business: Organic New Business. An allocator can choose to build a new business, rather than buy one. Building can be superior when there is no good external alternative available to buy, or if the organization has some key advantage it can leverage. Example: Google building Gmail, Uber building Eats.

- New Business: New Business M&A. The high risk, high reward form of M&A where an allocator acquires a business that operates separately from the existing core. Example: Facebook buying Instagram, Google buying YouTube.

- Shared Ownership: Strategic Investment. Strategic investments to guarantee certain services or partnerships for the core business are an oft forgotten yet effective way to allocate capital. These investments commonly yield benefits in supply chain, data access, or geographic expansion. Example: Softbank and Yahoo! partnering with Alibaba to enter China, Apple’s Advanced Manufacturing fund where the company has invested billions into suppliers like Corning, Finisar, and II-VI.

- Shared Ownership: Non-strategic Investment. Non-strategic investments are made purely for financial return. In other words, they are investments that have no expectation of creating specific business value to the allocator even if the allocator provides value to the investment company. Example: IAC investing in MGM during the depths of the pandemic.

- Return: Share Repurchase. Repurchasing company stock, according to Michael Mauboussin, makes the most sense when its stock is trading below its expected value and when no better investment opportunities are available. Many companies are too eager to repurchase shares given these criteria.

- Return: Dividend. Dividends are often viewed as consistent and irrevocable distributions to shareholders once established, although the best capital allocators use larger one-time dividends to great effect. Dividends can make sense for mature companies but should be viewed as more of a last resort given current tax treatment.

- Return: Pay Debt. As long as debt coverage is acceptable and strong opportunities exist in the first three categories, aggressive allocation to debt repayment is also usually a last resort.

- Cash: Cash & Equivalents. Cash is cash. Bitcoin does not fit here. At least not yet.

If we combine the menu framework with the lifecycle, capital allocation constraints and guidelines emerge dependent on a company’s stage.

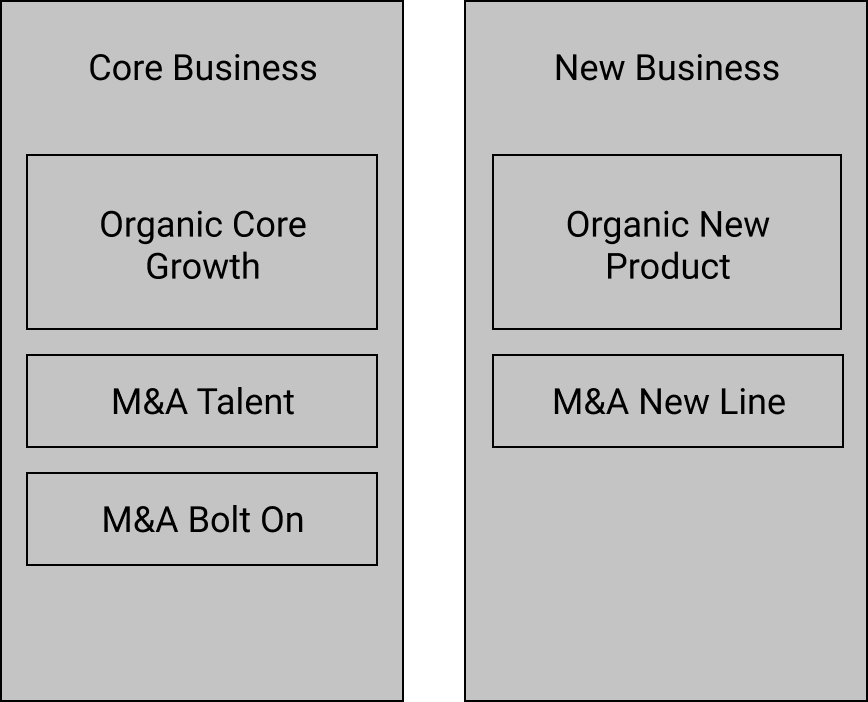

Startup Lifecycle Menu

Startups have the most constrained access to capital as well as the most constrained options for allocating that capital. Startup CEOs either invest in their core business or hold cash for runway:

Capital investment in anything other than finding escape velocity would be wasteful since the underlying business is not sustainable. Even within these options, funding organic core growth will overwhelmingly be the biggest allocation. This would seem to make capital allocation for the startup a foregone conclusion, but it’s not. Continuing to fund an existing business is an active capital allocation decision. Too many startup CEOs forget this and waste capital on ideas that aren’t working and pivot or cancel too late. Too many growth and mature CEOs do the same.

Allocation Rules for Startups

- Capital is not guaranteed to any project in the organization. There is no rule you need to invest in your existing business if it isn’t working. Startups often pivot. That’s a capital allocation decision. The CEO may see better returns building an entirely different business. Startups often shut down. That’s a capital allocation decision that says everyone involved is better off doing something else.

- Even if investments made today do not yield immediate profit, it should be expected that those investments return the principle and more over time. The capital base of a company represents all of the company’s efforts to create a valuable offering to customers built on some mix of IP, infrastructure, and working capital. Those investments must generate financial return over time in the form of after-tax profit that accrues to shareholders. It’s easy to forget this in the whirlwind of trying to establish a viable business. Great capital allocators relearn and remember this as the ultimate goal for building a successful business.

- Rules for early lifecycle companies transcend to later lifecycle companies. The first two startup rules should be carried forward through the growth transition and beyond. Progression deeper into the capital allocation lifecycle means the addition of new menu options, not the subtraction of fundamental requirements of allocation.

Measuring Allocation Success for Startups

Most startups, and nearly every venture-backed one, will generate minimal immediate financial return to calculate the effectiveness of capital allocation efforts. A strictly financial analysis of a startup misses the intangibles that indicate success. As Peter Drucker once said, “Securities analysts believe that companies make money. Companies make shoes!”

The point of any business is to create unique value for customers. A startup that allocates capital well makes shoes, or some other product, that customers love and can’t live without. Customer attachment is the most powerful signal to evaluate capital allocation at the startup phase.

Per rule two, attachment must eventually sustain growth that results in strong returns on allocated capital. If that doesn’t seem likely, see rule one. Per rule three, a startup CEO should never lose sight of customer attachment in the transition to the next lifecycle phase.

Growth Lifecycle Menu

Growth CEOs are afforded significantly more capital to capture large market opportunities that were proven in the startup phase. Market capture comes from customer acquisition and extending the company’s unique advantage. This means aggressive investment in the core business, but the growth lifecycle also opens the door to a broader menu of capital allocation options:

To the extent that a company’s customers or its unique advantage bump up against a new business or strategic opportunity, the CEO should be prepared to engage in that opportunity. The expansion of ways to allocate capital means growth CEOs need to understand getting paid for risk in a way startup CEOs can ignore.

Allocation Rules for Growth CEOs

- The core business eats first, although it may not eat at all. Remember rule one as a startup. There are no guaranteed capital allocations; however, the core should get first consideration from a growth CEO since there is assumedly a large market worth capturing through additional investment. At the growth stage, CEOs should have a strong sense for core business economics that allows for projecting future returns on continued investment as well as how much incremental capital can be invested at acceptable return rates.

- New business entry or strategic investment necessitates potential returns higher than the core. Entering a new business requires a growth CEO to consider opportunity cost. The capital to be allocated to a new business, whether through organic development or M&A, must either come at the expense of further investment in the core or cash reserves that would likely go to the core in the future. Therefore, a new business opportunity must carry potential capital returns higher than those of the core business to compensate for the risk of the unknown new business vs the known core.

- Building a new business organically is equivalent to building a startup and should be treated as such. This means the growth CEO and the “CEO” of the startup unit should adhere to the rules of startup capital allocation, especially returning capital over time given the organizational opportunity cost.

Measuring Allocation Success for Growth Companies

Successful growth stage capital allocation captures some target market with an expandable monopoly. There are a bevy of metrics growth CEOs can, and should, use to measure such progress: revenue growth, market share, cohort analyses, churn, NPS, LTV/CAC, etc.

The more interesting metric to assess capital allocation success at the growth stage is intangible, like creating irreplaceable value to measure a startup. Growth CEOs that find ways to grow the irreplaceable value they create for customers faster than price have succeeded in allocating capital well. Companies that do this for customers trend naturally toward monopoly and are well positioned to win the shareholder return game as a mature company.

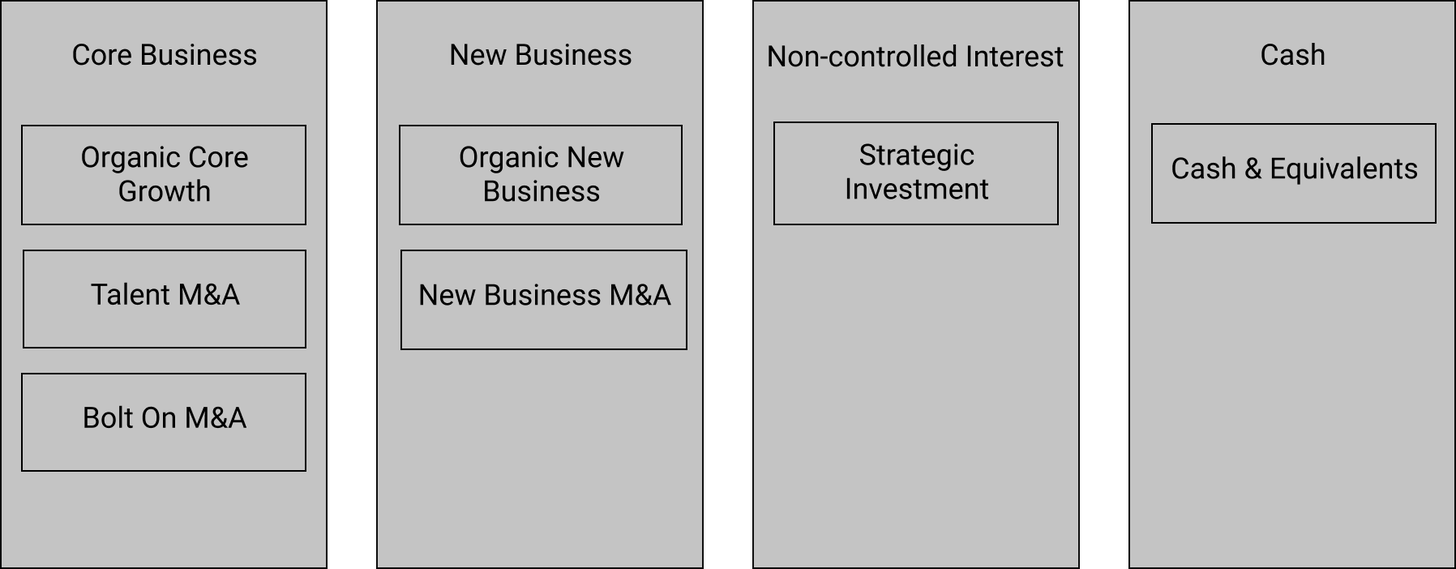

Mature Lifecycle Menu

By following the rules detailed for startup and growth lifecycle companies, all efforts to maturity should have had future shareholder return in mind. The many businesses that flame out in maturity fail because they didn’t have that objective in mind throughout the process. See any mature company that’s never generated a return on invested capital and continues to struggle doing so.

Whether deserved or not, mature company CEOs are afforded the full capital allocation toolset:

Capital return is the major additional tool for mature company CEOs. Some mature companies generate so much cash that they can’t redeploy it all back into growing the core or new business efforts. These companies can choose to distribute cash back to equity or debt holders.

While targeted repurchases can be a powerful tool for allocators, return mechanisms are often embraced too readily at the expense of incremental core and, even more so, new business investment. Executive incentives that reward short-term performance, adhering to investor demands, and general conservatism all play a role in mature company CEOs over using capital return mechanisms.

Any CEO that reaches this stage from startup has achieved an incredible feat. Rather than rules for allocating as a mature company, I’ll offer an observation: The worst thing a mature company CEO can do is lose the startup and growth allocator mindsets. Our current capital markets reward growth and innovation. That isn’t likely to change. Allocating capital to long-term profitable growth is, and will always be, only path to building a world-defining company.