A while back, I laid out an argument for why I think neurotechnology is an important and compelling field: it entails investigating, fixing, and enhancing the brain—the substrate of human phenomenological existence.

Here, I want to discuss the ethics of that field.

There are futures of neurotechnology I want, and futures I don’t. I want a healthier population with solutions to neurological disorders and other diseases; I want the loss of sensory function to entail a minor surgery, not a lifetime of disability; I want technology that works in the background to keep people feeling good, without making them dependent on it; I want amplified empathy and feelings of social connectedness; I want people to have agency over their identity by having a choice to enhance or change themselves if they’d like, absent social pressure; I want people to feel secure and confident that the technology which understands and influences their brain is trustworthy and positive.

I don’t want a world where neurotechnology creates a persistent anxiety about invasion of privacy; I don’t want those forsaken science fiction worlds where mind control is a reality and we’re all plugged into machines; I don’t want a world where we collectively resent neurotechnology, where we reflect on it as yet another one of those failures of culture and demonstrations of non-prescience that show up again and again in history.

I know the following: neurotechnology can mitigate suffering and neurotechnology can expand the horizon of experience.

I don’t know where technologies will be in 20 years, 50 years, 100 years. I don’t know if science fiction dystopias will materialize or not, but I do know that neurotechnology progress is occurring and will continue to occur. The challenge I therefore see myself and our culture facing is to manage that growth in accordance with prevailing cultural principles; in other words, to be ethical.

Introduction

Any sufficiently large adjustment to a complex system necessarily entails both positives and negatives—say, for example, introducing Facebook (large adjustment) to human society (complex system). In the technology world, with colorful pitch decks, superlative value propositions, and nine-figure acquisitions, it’s very easy to believe and be led to believe these negatives are trivial—or worse, they don’t exist. It’s easy to believe unwaveringly and with strong emotional conviction that technology is exclusively “good,” despite its obvious nuance. Neurotechnology is either no different, or it’s different in that we need to treat it with even more care.

In 2002, William Safire offered a definition of neuroethics that’s now widely referenced, showing up in nearly every resource on neuroethics I’ve seen. Neuroethics, he says, is “the examination of what is right and wrong, good and bad about the treatment of, perfection of, or unwelcome invasion of and worrisome manipulation of the human brain.”

Safire challenges an implicit axiom of technocracies, that progress is good. To build up a neuroethics from first principles, we must first take Safire’s cue to challenge this axiom: is progress in neuroscience and neurotechnology good? (Hint: it’s messy.)

Let’s make this question more specific by first splitting neuroscience/technology progress into categories: progress in basic neuroscience research, progress in the translation of neuroscientific knowledge to medical applications, and progress in the application of neuroscience to augment normal human capabilities.

The easiest of these three to discuss is the application of neuroscientific knowledge to medicine. To argue that it’s bad to mitigate abnormal suffering requires philosophical gymnastics—and the abandonment of multiple cultural values. I’ll go so far as to make the claim that, for our purposes, applying neuroscience to medicine is unequivocally positive.

This unequivocal positivity of medical neuroscience applications makes it fairly easy to justify progress in certain basic neuroscience research areas: basic research informs and provides the foundation for commercially-driven medicine. Hence, we can reasonably accept that basic neuroscience research is good, at least insofar as that basic research pertains to medicine. There remains the outstanding question of whether, for example, research into the neuroscience of consciousness is fundamentally positive. It seems to be a durable feature of humanity that we ask (yet seldom answer) questions about human cognition, emotion, and consciousness. This is as true now as it was millennia ago. I think, therefore, it’s fair to say that humans have a fairly inherent interest in understanding themselves.

The pursuit of the neuroscience of cognition and consciousness is just one particular flavor of these age-old inquiries, and it’s not going anywhere. Despite its romantic appeal, neuroscientific knowledge has teeth: the same neuroscience of motivation has both been used to induce negative addictions (like an addiction to social media) and been applied to treat emotional and cognitive disorders. It’s hard to argue that progress to the ends of the former isn’t bad; likewise, it’s hard to argue that progress to the ends of the latter isn’t good. We have to accept this complexity as inevitable and offer principles of ethics to manage it.

This nuanced balance of negative and positive shows up in our third domain to consider: progress in the use of neuroscience to augment human capacity. The arguments in favor include increasing productivity; expanding emotional, experiential, and sensory horizons; reducing the suffering inherent to modern biological humans; increasing the long-term survivability of the human species; etc. The arguments against: inducing a massive social rift; producing runaway artificial intelligence; violating “the natural order of things”; etc. Here’s the truth of it: arguments for and against both have merit. In attempting to assess whether augmentative neurotechnology is positive, we’re running a complex calculus of beliefs, truths, and logic—a calculus which has different rules depending on which mathematician you ask.

For two reasons, I think that augmentative neurotechnology is more-or-less inevitable: first of all, modern humanity has uniformly moved in the direction of augmentation (c.f. arguments that natural language, algebraic symbols, the printing press, modern telecommunications, etc. are all “augmentations,” as it were). Second, people are already working on neuro-augmentation, and momentum of that sort is hard to stop. Therefore, as with the case of basic neuroscience research above, the matter at hand is not to determine the “goodness” of augmentative neurotechnology but to encourage augmentative neurotechnology to manifest in ways that minimize its downsides.

In short, the technocratic axiom that “progress is good” needs to be extended to “progress is good and bad.” My goal, here, is to explore the particulars of this tension and to propose steps for how we can begin to manage it through the vehicle of Loup Ventures.

My Definition of Neurotechnology

In other pieces, I’ve offered fuller definitions of medical neurotechnology and non-medical neurotechnology. Here, I’ll partially recapitulate my previous definition of consumer neurotechnology since, as you’ll see below, this will be my ethical area of focus.

“Neurotechnology,” as used here, refers to devices/products that are explicitly designed to interact with neurons. These can be neurons in the brain, neurons in the spinal cord, neurons in cranial nerves, motor neurons in the body, or any kind of sensory neuron. What this notably excludes are products informed by neuroscience (or its close cousins, cognitive (neuro)science and psychology), but which don’t directly interact with neurons. In addition, neurotechnology includes the collection, storage, processing, and inference performed on neurodata—i.e., data collected from neurons (or other sources of information inherent to the brain).

The Benefits of Neurotechnology

Concretely, neurotechnology offers promise to solve medical problems implicating the nervous system—and since the nervous system is so critical to our biology, this encompasses many diseases and injuries. For the science fiction enthusiasts out there, consumer neurotechnology can enable consumers to control their technology in new ways; can enhance their learning; can assist in wrangling control over emotion. I’ve written about this extensively in Volumes I, II, III, IV, and V of a series on Consumer Neurotech.

Abstractly, opportunities in medical neurotechnology derive from the fact that the nervous system is an information pathway in the body, and therefore it’s a strong candidate for therapies. Opportunities in non-medical neurotechnology are due to the brain being the ultimate frontier for mastering ourselves. It seems likely that the quest for self-mastery is inherent to the human condition—neurotechnology comprises the tools and mechanisms to discover and act upon our mastery.

Therapies and Non-Therapies

Without a doubt, the most widely used neurotechnologies right now are therapeutic, and it’s difficult to debate their value (such as Nevro’s neurostimulation to treat chronic pain, deep brain stimulation to manage Parkinson’s symptoms, cochlear implants for deafness, and many more). Furthermore, both in the US and elsewhere, not only are medical devices and treatments heavily regulated, but various medical organizations have their own codes of ethics. The FDA has regulatory purview in the US over technologies or drugs that make medical claims (but not necessarily technologies that have biological effects, yet don’t claim to be a therapy), and HIPAA governs the use (and penalizes the abuse) of health data. The American Medical Association has a code of ethics, and additional opinions on more specific matters. Pertaining to neurotechnology directly, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons has their own code of ethics as well.

Therefore, even though the regulation is far from perfect and there’s a tradeoff between regulation and innovation, I feel confident that existing structures are suited to deal with the ethics of neurotechnology in medicine. Where I’m concerned is non-medical neurotechnologies, for which regulatory applicability is less clear.

Non-therapies have fewer protections. What’s more, the science fiction thought experiments both futurists and anti-futurists like to run implicate non-therapies more strongly than therapies: here, I’m referring to networked brains, digitally uploaded consciousness, etc. Let me be crystal clear: these don’t exist yet, and it’s possible they never will. But, technology that moves in this general direction has the most ethical pitfalls ahead of it, so that’s where I think it’s most important to help construct guidance.

Enhancements

Many non-therapies are enhancements (although an example of a non-therapy neurotechnology that isn’t an enhancement is, say, a performance test that uses neurotechnology to collect its information).

Employing what’s likely an imperfect taxonomy, enhancement can be split up into three categories: cognitive, environmental, and social/moral.

Cognitive Enhancement

“Cognition can be defined as the processes an organism uses to organize information” (Bostrom and Sandberg, 2009). Some examples of cognitive subsystems—i.e., different aspects of cognition—include working and long-term memory, attention, executive processing, language, perception (e.g. auditory, visual), etc. Bostrom and Sandberg (2009) offer a fairly extensive overview of the various types of cognitive enhancement discussed in the literature. Examples of cognitive enhancement include education (evidence for this point: try naming an element from the above list of cognitive subsystems that education doesn’t improve), mental training (such as the Method of Loci), existing computer software and hardware (e.g. data visualization, data search, and even the simple duo of keyboard and word processor), pharmaceuticals (e.g. Adderall, Modafinil), genetic modifications (either non-transgenerational somatic gene editing or transgenerational germ-line gene editing), pre- and perinatal enhancement (supplementing a mother’s diet during gestation), neuropriming/neuromodulation (electrochemically modulating the state of the nervous system so as to induce a particular effect, such as faster learning), brain-computer interfaces (currently, these don’t yield much in the way of enhancement; however, in the future they could conceivably be the source of profound enhancement, assuming that future BCIs enable much higher information bandwidth in human-computer communication than modern BCIs allow), and sensory/perceptual prostheses (such as a retinal implant that allows the wearer to “see” electromagnetic radiation in the infrared spectrum).

Enhancement of Environmental Control

This is more of a gestalt domain than a fundamental one—I’ll motivate it simply with the idea of using a brain-computer interface to modulate a Nest, and therefore the temperature in your house. This is gestalt insofar as it’s enabled a) by the presence of brain-computer interfaces that can decode the necessary neural signals, and b) the presence of Internet of Things-enabled environments. We can also imagine this in the context of virtual reality, where the environment is controlled with software, and therefore the requirement is reduced to just the presence of a BCI with sufficient neural decoding capabilities.

Social/Moral Enhancement

Social and/or moral enhancements are already familiar to us. Limited quantities of alcohol lower inhibitions and therefore make it easier to socialize (or so the cultural belief goes). Neurofeedback can be used to modulate people’s responses to emotional stimuli. Oral contraceptives increase oxytocin levels. One can imagine behavioral- or neuro-engineering that up-regulates acts of kindness, a sense of empathy, “moral” behaviors (e.g. not lying), etc.

Interestingly, a study by Riis, Simmons, and Goodwin (2008) presents evidence that people are uncomfortable with enhancing traits that are “core” to one’s sense of self (at least insofar as the study’s college-student subjects can generalize to “people” at large)—many of which traits fall within the domains of sociality and morality. As examples, only 9% of polled subjects were willing to enhance “kindness,” and 13% were willing to enhance “empathy,” both of which topics the subjects rated as highly core to their identity. By contrast, 54% of subjects were willing to enhance “foreign language ability,” which subjects rated as not being very core to their identity.

Therapies That Become Non-Therapies

The considerations around non-medical neurotechnologies include not just the devices themselves, but also the data. In principle, health neurodata (which is governed by HIPAA) can transition into non-health neurodata. Many neurotech applications, like EEG or ECoG data for epilepsy detection, are going to entail the collection of neurodata for use in health applications. It’s natural to want to take that health data and use it to infer health-related things about people, and perhaps investigate large-scale anonymized datasets (e.g., what are the demographic or lifestyle factors that correlate with increased occurrence of a particular type of epileptic seizure?). It’s very easy to transition from here, though, to asking questions like: do people with certain EEG patterns show higher incidence of recidivism following incarceration and/or restorative justice processes? As we see, health neurodata may be applied to derive medical insights, but it can also be applied in much more controversial and ethically dubious territory.

One question of mine, to which I don’t have an answer right now, is whether HIPAA prevents the eventual use of health neurodata for non-health applications. HIPAA places restrictions on when/why data can be shared with third parties, and these restrictions apply to “protected health information,” which is defined as information that

- “Is individually identifiable health information, whether oral or recorded in any form or medium (e.g., narrative notes; X-ray films or CT/MRI scans; EEG / EKG tracings, etc.), that may include demographic information, and

- Is created or received by a ‘covered entity,’ that is, a health care provider, health plan, or health care clearinghouse, and

- Relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual, to the provision of health care to that individual, and/or to payment for health care services and

- Identifies the individual directly or contains sufficient data so that the identity of the individual can be readily inferred.”

I don’t know whether this applies to, for example, EEG data that was collected originally for medical purposes, but then anonymized and used for non-medical ends.

The danger here isn’t immediate, and it might not even be worth spending time dwelling on; I bring it up for the sake of demonstrating the complexity in the ethics of neurotechnology. More broadly, I think it’s critical to acknowledge the speculative nature of planning for non-medical neurotechnology ethics. By intention, I’m discussing technologies which don’t exist yet, except perhaps as proofs of concept in laboratories, or embedded deep-down in active imaginations. It’s impossible to predict when (and perhaps if) the problems above, and below, will be pressing; for example, when a consumer-ready technology that can non-invasively decode mental speech will be brought to market.

My philosophy is that it’s better to preempt than to respond. This means that, by necessity, we have to imagine future scenarios. Here, I owe my reader a warning: future scenario imagination is inherently alarmist, but it seems like a reasonable tradeoff to me, since the possibility of “not as much innovation, not as quickly” is better than “too much innovation, too quickly.” I’ll let Facebook’s current situation speak for itself.

A Unified Framework

With the above in place, I can now lay out the framework I plan to apply to the ethics of investing in neurotechnology.

1. The Wall of Discretion

There exists a mental wall: behind this wall, we live and hide our inner lives. In front of this wall, we vocalize ourselves. The vocalization is the input to the morality function our culture computes: i.e., we’re morally assessed based on our actions, and not our thoughts and our feelings inside that don’t manifest externally. Neurotechnology threatens this sacred wall by proposing the possibility to characterize the mental contents within, ostensibly with or without our knowledge or consent. I call this wall the Wall of Discretion.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it in their entry on neuroethics:

“In the past, mental privacy could be taken for granted: the first person accessibility of the contents of consciousness ensured that the contents of one’s mind remained hidden to the outside world, until and unless they were voluntarily disclosed…Over the last half-century, technological advances have eroded or impinged upon many traditional realms of worldly privacy. Most of the avenues for expression can be (and increasingly are) monitored by third parties. It is tempting to think that the inner sanctum of the mind remains the last bastion of real privacy.”

Let’s consider a thought experiment: suppose that Instagram, with its likely ability to classify its own content semantically and to record through the Instagram app how much time you spend looking at each type of content, can build a fairly sound psychological profile of you. How does this make you feel?

Now, consider a (near?) future in which Facebook builds a device that can transcribe the words you’re thinking. How do you feel?

If you’re like me, and I suspect most people are, the latter scenario is frightening. Maybe even chest-tightening. This is because we’re deeply familiar with putting our external characteristics and behaviors on display and keeping our internal characteristics and behaviors hidden.

Our psychological profiles are almost meant to be out in the wild; we pride ourselves on our personality traits, and “pride” assumes there’s someone out there who will notice the thing we’re proud of. What’s identity without other people to show that identity to? In contrast, internal language, emotion, intuition, and gestalt percepts are meant to be internal. In other words, we all have a subjective feeling that our thoughts and emotions belong inside.

To provide further evidence for the distinction between “internal” and “external,” and therefore to further evidence the Wall of Discretion model, consider Myers-Briggs scores. A common question for a new friend is: “What’s your Myers-Briggs?” Horoscopes have a place in pop culture for a reason, too.

Let’s look at dating apps. They all contain demographic information that defines our preferences and provides other people with a way to determine quickly if they find us appealing. Sometimes it goes beyond demographics, such as with OkCupid, which asks its users an intricate set of questions to try and create better matches—none of which is to mention that some dating apps even have dedicated fields for astrological signs in their profiles.

It’s evident that we have external selves and that we share those external selves widely. What are the transition points, or the channels, by which we take “stuff” from the inside and bring it outside? One interesting example is making a post on Facebook. Consider the painstaking nature of this process (assuming we’re writing a post with meaningful semantic content, like a political post or a life update or a bit of wisdom you feel compelled to share with the world, as opposed to a photograph from your trip to the Grand Canyon last month). In first person: I sit down at my computer, I open up the tab, I stare at the empty box for a minute or two, I type a few words, delete them, then repeat and gradually craft the post—it’s a meticulous process. I make my edits, I decide which emoji I want to insert based on the reactions I think they’ll evoke, and I choose whether or not to include a photo for emotional impact and/or humor effect. I’ve made quite a few decisions at this point about how to translate what’s behind my Wall of Discretion, both semantically and emotionally, into what’s released externally.

Another interesting case-study in the Wall of Discretion (WoD) is alcohol. People regularly consume alcohol to make it easier and more natural to move things from within the WoD outside of it. Many of us have a drink or two at social events in order to feel more social (because alcohol lowers inhibitions). There’s much cultural humor (and many anecdotal stories) about people over-imbibing and sharing what’s inside their WoD too freely, then regretting it once they’ve returned to a normal mental state—take, for example, the canonical drunken love profession.

It’s also reasonable to ask how we decide what types of things are inside the WoD. With intuition and personal experience as my evidence, I’d say the contents within the WoD can be dichotomized: unintentional and intentional. Unintentional contents include emotional reactions, implicit bias, physical attraction, etc. Even linguistic thoughts can be unintentional: “This thought popped into my head the other day” implies a lack of agency. The intentional contents behind the WoD include deliberate thought processes; beliefs, values, and morals you’ve explicitly chosen to hold; internal decisions you’ve made. Importantly, also within the set of intentional contents are our conscious reactions to unconscious (or unintentional) contents. In other words, it’s not my choice if I feel an emotion towards a sad scene in a movie; but, I can decide how to handle the presence of that emotion, and whether or not to externalize it. Thus, if the contents inside of my Wall of Discretion were exposed, not only would someone be aware of that emotion, but they’d be aware of how I decided to react to it – and that reaction is a measure of my character.

Recapping, we seem to enjoy and/or value breaking the Wall of Discretion in certain scenarios, primarily social:

- Direct communication

- Mating and signaling social status

- Signifying that we’re comfortable with someone

- Meeting new people & interacting with many people

From all of this, I see five core principles of the Wall of Discretion.

- Human communication is the intentional transmission of information through the Wall of Discretion. Whenever we communicate, we take a message from inside our conscious realm and express it outwardly; we pass that message through the Wall of Discretion.

- The morality of individuals within our society is judged based on what they’ve transmitted through their WoDs—i.e., their actions, behaviors, and stated beliefs. This has to be the case, since by definition, what’s inside of the Wall of Discretion is hidden and therefore unobservable by other people.

- What we choose to filter through our WoD varies depending on the recipient: certain information, such as sexual preferences or health status, we’ll share with some people but not others. This follows directly from the observation that human communication is the transmission of information through the WoD: we communicate different information to different people.

- We’re not used to internal WoD contents being observed. Polygraph tests and torture are examples of WoD-violating practices that we culturally frown upon or outright ban. The stuff of our inner sanctum—emotion, internal monologue, bias, desires, verbal thoughts that pop into our ahead—is never observed by other people.

- Violating the Wall of Discretion can lead to the observation of unintentional mental states (i.e. the conscious manifestations of unconscious processes) and our intentional reactions to those unintentional states. Emotion, for example, isn’t something I decide. It occurs (i.e., it derives from neural processes I don’t have conscious access to), and then I observe and react to it consciously. The same set-up applies for implicit bias: it occurs, and then I react to it. Unless I choose to communicate my reactions, they stay behind my Wall of Discretion. Therefore, if my WoD is violated, my intentional reactions to unintentional states can be observed.

With polygraphs, we’ve finally brought neurotechnology into the WoD picture: since the WoD is a theoretical heuristic for psychological processes that sit on neurobiological substrates, neurotechnology can threaten the internality of contents within the WoD. Here are some considerations:

- Remote vs. local neurotech: If neurotech evolves such that it can deduce some or all aspects of the WoD internals without actually requiring a device on or in someone’s head, then it will be very hard to prevent nefarious usage. In contrast, if neurotech evolves such that it can transcribe WoD internals only if it’s on the head or very nearby, then covert monitoring is less feasible.

- Willful vs. non-willful neurotech: if neurotechnology paradigms require the subject to engage in a predefined activity in order to interpret their neurodata (which is often the case with EEG and fMRI), then the subject can simply choose not to comply and barring torture, there’s nothing to be done. On the other hand, if neurotechnology can simply read out internal monologues (very important note: this is not possible right now), then things get dicey.

The worst case is the intersection of remote and non-willful neurotechnology: if such technology comes to exist at some point, it will probably enable profound encroachment upon our Walls of Discretion.

This discussion of the Wall of Discretion would be incomplete without acknowledging the potential benefits of a neurotech that can cleanly cut through the WoD. Of course, there’s the science fiction dream of direct brain-to-brain communication, which is a means to facilitate profound human connection. There’s also the possibility for, as an example, a psychotherapist to gain detailed insight into a patient’s negative thought processes—down to the words, even—granted the patient’s consent. We can even consider the scenario where an individual has been wrongly convicted, and can willfully submit to a futuristic “truth detection” technology in order to exonerate themselves.

Concluding my thoughts on the Wall of Discretion: technology that can be used to non-willfully and remotely observe internals behind the WoD should not exist, because it invades privacy above and beyond what we’re comfortable with culturally. That said, it’s feasible for culture to move in a direction where we’re collectively more comfortable with the reality of ad-hoc internal WoD access. I can’t imagine a reality in which I sit down at a coffee shop and intrude on someone else’s inner world—frankly, I see in that possibility a mutually assured destruction. And so, here’s a hypothesis that’s morbidly positive: even in the eventuality of non-willful and remote WoD-breaking technology, I don’t think it will be adopted at scale because if it does, everyone’s worse off.

One final note: the Wall of Discretion doesn’t capture every issue inherent to neurotechnology. Rather, in my view, it’s an elegant way to conceptualize what is time-asymptotically at stake. For a much fuller treatment of neuroethics, I’d strongly encourage the reader to spend some time studying the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry on Neuroethics (or reach out to me about a particular area of interest, since I’m not an expert and I’ll enjoy learning with you). In particular, I’ve omitted discussion of informed consent, the details of data privacy, the moral implications of enhancement, socioeconomic gaps, and neuro-essentialism.

2. Thoughts, and Decoding Them

The mechanism by which the Wall of Discretion can theoretically be broken is by “decoding thoughts.”

This discussion begins with the ideas of the conscious and the unconscious because they underlie the intuitive definition of “thought.” For my purposes here, I’ll just characterize the state of “consciousness” as something that we can report ourselves as possessing; we have some awareness that it’s occurring. “Unconsciousness,” on the other hand, is characterized by the fact that we can’t report it, and we aren’t aware when processes of the unconsciousness are occurring, nor we can we describe those processes.

Unconscious processes strongly influence conscious processes, so the model of considering them separately is inherently flawed. It’s useful, though, because we don’t actively perceive unconscious thought factoring into conscious thought (by definition), and therefore much of the intuitive emotion behind “thought” really pertains to conscious processes, which are in turn influenced by unconscious processes.

What, then, does it mean to decode “thought”? Put another way, how might we break the Wall of Discretion using neural signals, as opposed to through intermediary modalities such as language (writing and speaking), observing behavioral data, dance, the visual arts, etc.? To make this a well-posed problem, we have to identify concepts or states that can be deemed as entities and then identified through the observation of neural substrates. Using the English descriptions of these concepts (instead of describing them by a hypothetical set of neural interactions, such as “population A of neurons exhibits a firing rate normally distributed around mean firing rate x…”):

- Emotion (e.g., location along the Pleasure-Arousal-Dominance axes)

- Language

- External visual information (information we observe through our eyes)

- Internal visual information (imagined sight)

- Spatial knowledge and sensation

- Procedural knowledge (e.g., how to play a Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata on the piano)

- Impending decision (e.g., the selection between coffee beverages)

- Implicit bias

- Sexual and romantic preferences

- Auditory information

- Motor intention

Listed above are some of the types of contents we keep within, or transfer out of, the Wall of Discretion. It’s these that non-medical neurotechnology promises to expand and threatens to uncover.

3. The Wall of Discretion Should Remain Intact

The Wall of Discretion should not be broken unless someone wants it to be, in which case they can only exercise that will over their own WoD. This is my view for two reasons (which need more research to turn into well-evidenced arguments, rather than strings of hypotheses).

Morality preserves life

- Human life ought to exist (axiom);

- Culture enables prolific human life (hypothesis);

- Morals keep cultures together by facilitating group cohesion (hypothesis);

- Morals depend on filtered human emotion and thought; i.e., social pressure acts to moderate and counterbalance internal urges (critical hypothesis [note that this hypothesis depends on our current biological configuration in which there are competing signals, such as those from the neocortex and the limbic system]);

- Therefore, if the Wall of Discretion is broken unwillingly and at scale, then under current biology, it’s unclear what happens to moral systems, which in turn poses a threat to culture and therefore to the proliferation of human life.

We should minimize suffering

- We shouldn’t create suffering (a moral axiom);

- The invasion of privacy has a distinctly negative feeling, and can, therefore, be considered as a form of suffering (personal observation and subjective claim);

- Breaking the Wall of Discretion involuntarily is interpreted emotionally as having one’s privacy invaded (personal observation);

- Therefore, to minimize suffering, we shouldn’t unwillingly break the Wall of Discretion, because to do so is to cause suffering.

So, going forward, I assume that the Wall of Discretion should stay intact (and that willful breaking of the WoD is better than local non-willful breaking of the WoD, which in turn is better than remote non-willful breaking of the WoD).

Ethics and Investors

If there’s a practical way to quantify the regard we have at Loup Ventures for the ethics of our investments, it would be by measuring the number of hours of phone conversations we’ve dedicated to it (note my use of “hours,” not “minutes”). At Loup, we want to be investing in technologies that are, in aggregate, a positive force. Doug Clinton, one of our Managing Partners, has put in significant work to articulate a broader code of ethics, and it boils down to the following statement: Invest in high-integrity founders making products people love and that our Limited Partners will be proud to back.

Why do we care about this? It’s unclear yet if there’s strict business value, but there’s definitively a social obligation. We have an obligation to society to be conscientious of the technologies we back, and of our resulting impact. I hold this obligation to be true of anyone—investor, engineer, poet, painter, or otherwise.

As investors, we have certain leverage points that others don’t, meaning that our efforts in neuroethics can go a long way.

- We’re connected to many stakeholders: startups, regulators, consultants, other investors, employees, entrepreneurs, etc.

- By virtue of the enabling relationship between venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, the venture community can set the standards of conduct for entrepreneurs.

- As investors, we have downstream impact on public sentiment through the successes (and failures) of our portfolio companies, and even through direct press.

- We write checks that help entrepreneurs realize their products.

Taking Action

With the Wall of Discretion as the underlying principle and a quick argument for why VCs can and have to be effective ethics gatekeepers, I can now begin to think about how Loup can work to uphold ethical neurotechnology development.

Broadly, we want to create a pipeline for ourselves that ultimately gives a green light or a red light to a particular neurotech investment opportunity. An ethically sound neurotechnology company doesn’t mean we’ll invest, but an unethical company means we won’t.

We’ve been engaging in an internal process to generate this pipeline. The procedure has included reading, talking to experts (ethicists, other investors, companies, scientists/engineers, etc.), and synthesizing the results of this research. Once we have a pipeline in place, we’ll publish the principles behind it and maybe the pipeline itself (in support of transparency and in advocacy of ethical neurotech). We’ll articulate this pipeline to our LPs, to our existing neurotech portfolio companies, and to prospective neurotech portfolio companies.

Ethics are best upheld by social forces, and ultimately collective opinion decides ethics as opposed to individuals (or individual organizations). That said, we chose to start this process as an internal push rather than external push since the feedback cycle on principles of ethics is much more efficient internally. Even though it was developed internally at Loup and not with formal external input, the forthcoming end-result of this internal process—a set of guidelines for our investments in neurotechnology—is something that can benefit the entire community; at the least, it can drive conversation and inspire additional collaborative work.

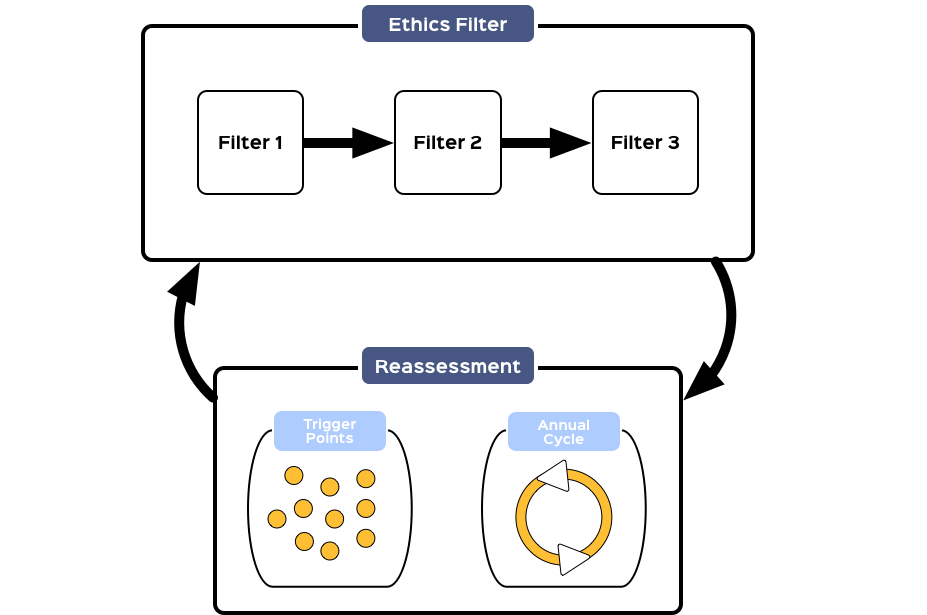

Sketch of a Pipeline

We haven’t finished this yet, but we want to share our progress so far. The initial model is to use a three-filter pipeline:

“Filter 1” contains a set of criteria for whether or not it’s worth introducing a given neurotechnology to society.

“Filter 2” checks a prospective investment’s work against a blacklist (no-go), graylist (exercise caution, but not immediately no-go), and whitelist (all clear) of neurotechnologies and their applications (this idea was inspired by conversations with Boundless Mind, a behavioral engineering company that has put substantial thought into the ethical applications of their technology). This is a list we’ll develop internally, and if other funds adopt a similar pipeline, they’ll have to apply their own philosophies and judgments to generate their unique versions of these lists. If we encounter a technology that isn’t already listed, we’ll have a process for making a de novo decision, and of course, use that decision to expand the lists appropriately.

“Filter 3” comprises a checklist of items that our portfolio companies will have to complete either before our investment or once it’s been made.

All three of these filters, and the structure of the pipeline itself (i.e., the utilization of three linearly-arranged filters), needs to be adaptive. To make it adaptive, we will a) define certain technological trigger points that would cause us to re-evaluate our pipeline or particular components of it, and b) we’ll implement an annual review and reconsideration of the pipeline.

Filter 1

As a first-order filter for making ethical investments, we can select a set of criterion for whether a neurotechnology is worth introducing to society. In my view, the burden of proof should be on the technology: we assume a technology shouldn’t exist until convinced otherwise. Make no mistake, this is a strong philosophical stance: augmentative neurotechnologies shouldn’t exist unless they strictly improve certain “endpoints” (e.g., human performance, human well-being) for a definable population. Note that this coincides well with what makes a business successful.

To determine that a neurotechnology ought to exist, we need to see evidence that

- There’s positive value added by the technology;

- The technology doesn’t have reasonable feasibility of unwillingly breaking the WoD (particularly in a remote, non-willing manner); and

- The technology doesn’t facilitate negative mental impacts via means other than WoD breaking (e.g., reducing the intrinsic enjoyment of an experience through over-quantification).

Filter 2

Filter 2 is comprised of a blacklist, a graylist, and a whitelist. We’re not ready to put these lists out to the public yet since they’re not complete, but to give an example of something that’s blacklisted: we won’t invest in neurotechnology that’s primarily intended to be weaponized. As another example, we won’t invest in neurotechnology that’s being directly applied to decode someone’s internal contents against their will (e.g., a hypothetical lie detection test that works without the subject’s consent).

Filter 3

The third filter is less stringent; it’s more about the continued maintenance of ethical practices within the prospective portfolio company. For example, we could require that the prospective CEO has a conversation with a trained neuroethicist to discuss ethical implications of their technology. We may further require a simple but informative neuroethics training for new hires at the prospective portfolio company. Essentially, Filter 3 covers operational elements that aim to build a culture of ethics into our portfolio companies. If the management team of a company expresses a commitment to completing this checklist and has passed the first two filters, then we would give them the final ethics green-light.

Implementing trigger points

Above, I mentioned that one of the characteristics of this pipeline is its built-in adaptability. That largely comes from a “trigger-point” model, where we define then continuously update a set of triggers that would cause us to think carefully about a given neurotechnology and understand the nuances of its development and applications in order to make more precise ethical determinations in that domain.

Some trigger points could include:

- The ability to reliably modulate emotion on-demand. The better case of this is that this can only occur with the consent of a user; the worse case is if this can be done without consent because that’s an unwilling manipulation of contents behind the Wall of Discretion.

- The ability to fully decode covert speech with a non-invasive device. A fine case of this is if it can only occur with the consent of the user since this constitutes a willful breaking of the WoD. The worse case is if this is feasible without consent, in which case we have unwilling WoD breaking.

- The proliferation of consumer EEG devices where data is centrally collected and privacy is put in the hands of business organizations, and furthermore, the neurodata can be demonstrated to yield insights into real-time characterization and can predict user actions above and beyond behavioral data. The fine scenario is if users are made aware in clear, understandable terms the capabilities of a system that performs these actions, and are kept up to date on new capabilities. Additionally, users should have the ability to opt out of prediction, characterization, and the related data storage at any time, and should be able to access reports on if/how their behavior has been manipulated using insights from the neurodata. These conditions ensure that this scenario is a willful breaking of the WoD. (A note: one way to verify the “fineness” of this scenario is to look at the distribution in a population of comfort with a given application or software capability, on a scale of very uncomfortable to very uncomfortable. If the comfort/discomfort distribution is similar to existing WoD-breaking technology, like targeted advertising, then we can be confident that this hypothetical neurotechnology is alright—assuming, of course, that we’re willing to consider statistics-level sentiment as a signal on which to base our ethical determination.) A worse case is if users are unaware of the capability of the hypothetical software that uses EEG data to make decisions since this covertly breaks the WoD.

- The hyper-quantification of subjective experience. The fine case here is invisible-but-consented quantification of subjective experience that can be used in the background of a software application, physical environment, or other another service (e.g., the gym) to facilitate positive emotion. In this case, it’s a willful breaking of the WoD. The worse scenario is consented and visible quantification of subjective experience, since it might reduce the intrinsic enjoyment of experiences. I tend to favor technominimalism under the anecdotally-informed hypothesis that human experience is richest in the absence of overt technological interaction (“natural = good” isn’t a sound justification, nor do I buy it, although I need to flesh out a better-formed argument for technominimalism). In general, the goal is to keep “neuroinsights” and neurodata out of people’s fields of view.

- Cognitive enhancement that is a) extremely expensive, b) creates a meaningful increase in performance, and c) is unlikely to reduce in price anytime in the near future. This is a trigger-point because it invokes the question of a socioeconomic split. This is most strongly a possibility in the case of an invasive, enhancing neurosurgery that costs tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars out of pocket, since it wouldn’t be covered by insurers.

- Weaponization of any form of neurotechnology. A discussion of the pros and cons of weapons is beyond the scope of this piece, but our heuristic is to not fund technologies that can and/or will knowingly be used to induce suffering.

- Introduction of any neurotechnology that strictly decreases the probability of well-being or the economic success of an individual (e.g., using lie detection as a hiring tool). Note the importance here of considering the individual over the corporation.

Conclusion

What I’ve undertaken here is an attempt to do the following:

- Explain why neuroethics is worthwhile to think about in general;

- Explain why neurotechnology investors have particular leverage in supporting ethical neurotechnology;

- Define an underlying principle/idea that can be used to guide the discussion of the ethics of neurotechnologies; and

- Sketch out a pipeline for performing ethical vetting on neurotech investments.

My thinking on the ethics of neurotech, and how I work with my colleagues at Loup to actionably implement this abstract thinking, is fluid and responsive. I encourage you to reach out with any feedback, ideas, and/or criticisms.

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest or may invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we may write about companies that are in our portfolio. As managers of the portfolio, we may earn carried interest, management fees or other compensation from such portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making any investment decisions and provided solely for informational purposes. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections and the content on this site should not be relied upon. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.