Most investors think about the world in terms of growth or value. Growth investments tend to be in companies relatively early in their growth curve with high revenue growth. Growth companies are often unprofitable as they invest heavily to capture the dominant position in their market. Growth valuations are based on assumptions about future growth and profitability. A value investment assumes some company is underpriced relative to its intrinsic value. Traditionally, value investments are in companies that are relatively mature with profits off of which to value the business.

In either case, an investor’s job is to buy an asset that should be worth significantly more based on its underlying earnings and assets. Growth investing is about future underlying earnings and assets, assuming they come to fruition. Value investing is about current underlying earnings and assets, assuming they are sustainable.

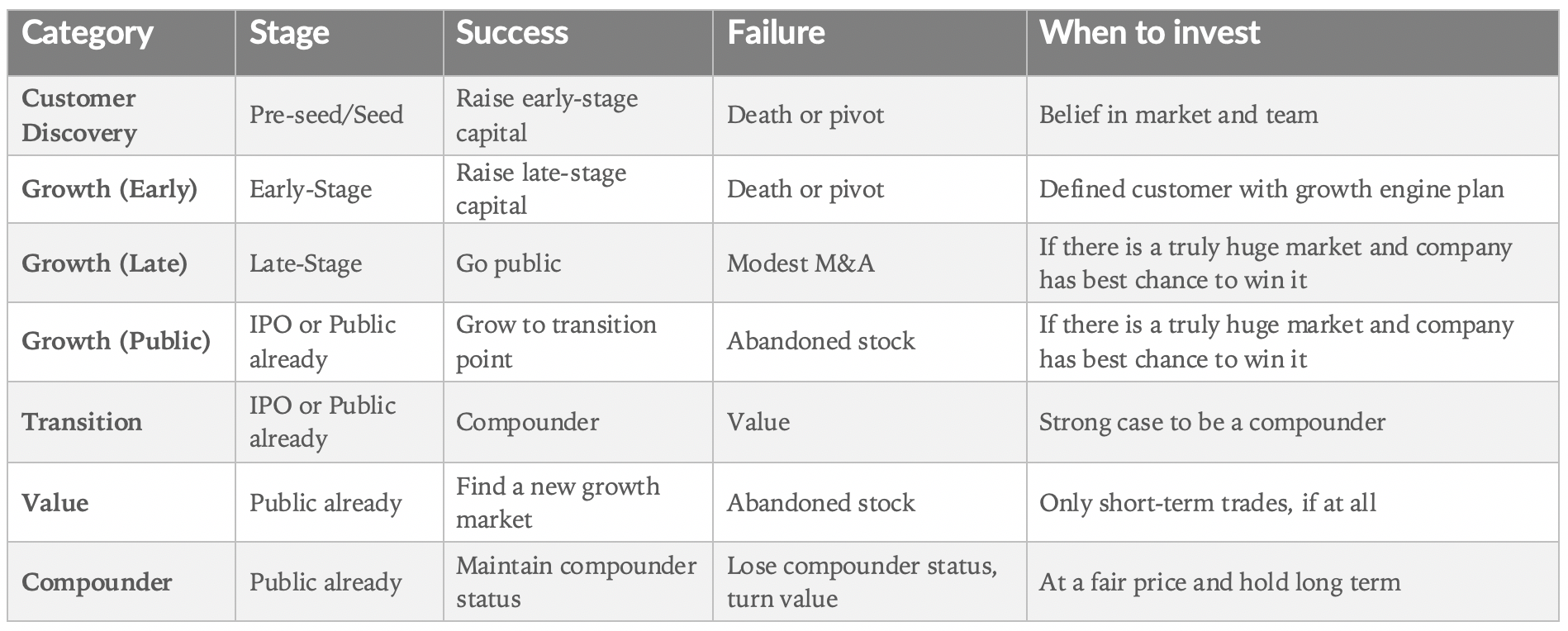

We believe this framework obscures the reality of tech investing (perhaps all investing, although we are not experts beyond tech), where there are five categories of investing, not two:

- Customer discovery

- Growth

- Transition

- Value

- Compounder

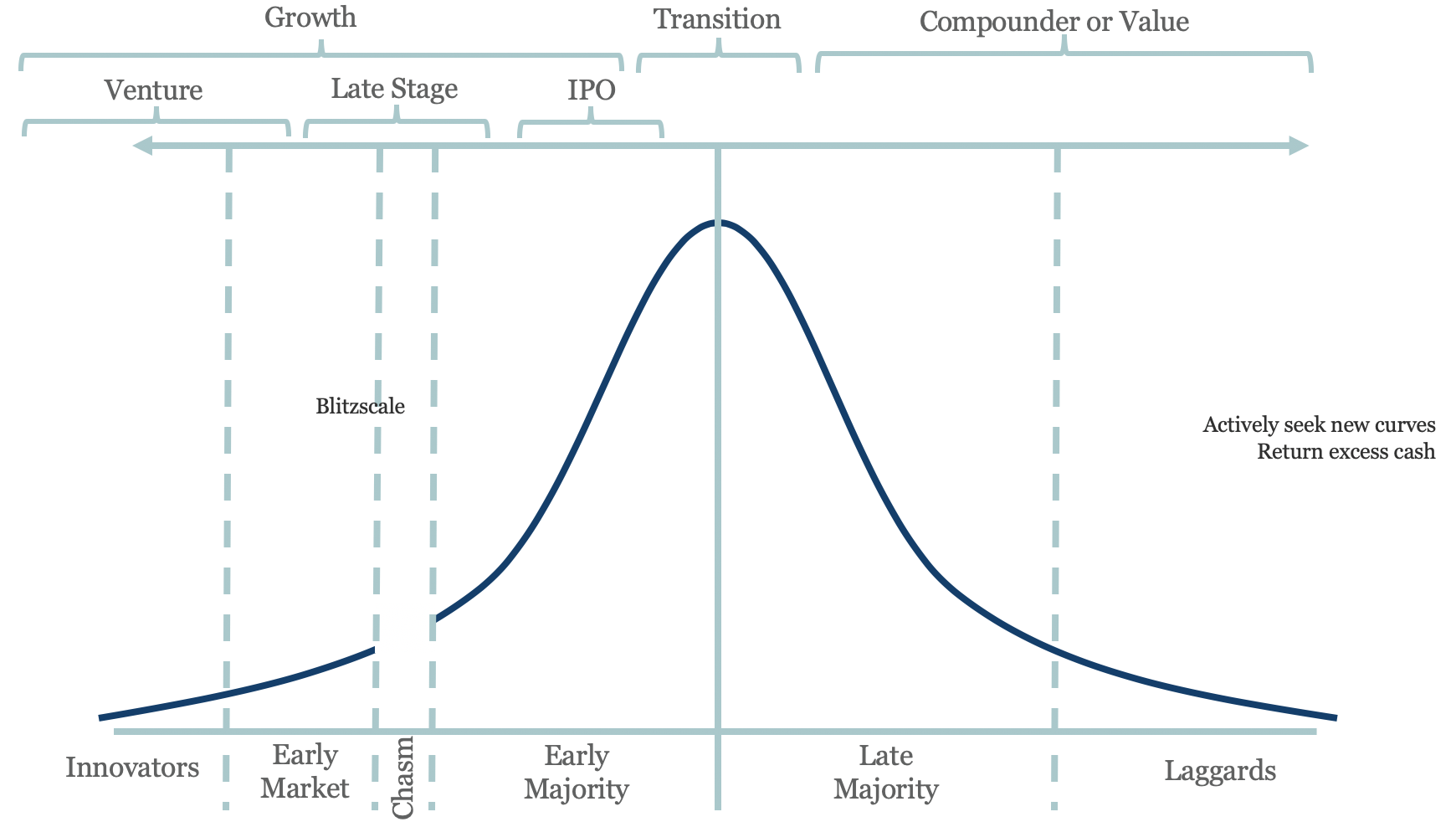

These categories of tech investments are also the natural progression of a technology company along a market growth curve via the work of Everett Rogers, built on by Geoff Moore. Understanding these categories is important because if a tech investor doesn’t understand the category an investment fits in, their expectations will veer from reality and results will disappoint.

A true technology company is either growing rapidly or harvesting tremendous profit from winning a huge market. Otherwise, the company is dying.

Five Categories of Tech Investing

Customer Discovery

Customer discovery is where pre-seed and seed-stage investors live. These investors fund companies that have yet to answer the core question: for whom does our product solve a real problem? Pre-seed and seed investors are looking for a potentially large market with a decent team capable of figuring out if their solution addresses a real customer need. Growth isn’t the key goal of this phase — defining your customer is — though growth is the key indicator of finding a real customer need.

The customer discovery phase is where every company must start, selling to innovators willing to try new solutions. Most companies die in this phase, some pivot to try to serve different customers, some pivot to completely different ideas, and a few graduate to the growth phase.

Growth

Growth investing is what most commonly comes to mind for tech investing. This makes logical sense because innovative technology companies should be growing rapidly if their products resonate with the market. However, growth investing spans a wide swath of an industry growth curve — from early market through much of the early majority — and each subset has particular nuances.

Growth investors can be early-stage venture investors who are looking for companies that have found customers for their solution and need to build a repeatable success engine for bringing those customers into their business. Early-stage investors typically deal with companies addressing the early market phase of the curve.

Growth investors can be late-stage venture investors looking to supply companies that have a proven success engine with large amounts of capital to scale quickly and win the market. Late-stage investors typically deal with companies in the late early market or the beginning of the early majority of a growth curve.

Growth investors can also be public market investors. Generally, these investors look for companies similar to late-stage venture investors, but with diminishing capital requirements as the companies work deeper into the early majority of their growth curve and transition to sustainable businesses.

In our view, the best growth investments come when the market is in the later stages of the early market to the beginning of the early majority period and the investor community under appreciates the true size of the market. Any time the investor community fully appreciates or, even worse, over appreciates a market opportunity, the potential for returns is diminished because the opportunity is factored into the valuation of the equity.

Transition

Of all the tech investing categories, we believe the transition category is the least well understood. As a tech company matures along its market growth curve, it has to demonstrate a profitable underlying business for the company to be self-sustaining. Every tech company eventually reaches a phase in its lifecycle where investors don’t really view it as a growth company anymore, but the company also hasn’t yet crossed into the value or compounder category. Per our mantra above, a true technology company must either be growing rapidly or harvesting profit. The transition phase is the period of shifting from the former to the latter.

Transition companies generally have a strong market position, otherwise, they would have died along the way. They’re also usually still “growth” companies by the raw numbers. The minimum hurdle to be a growth company as a public entity is 20% annual revenue growth, although many investors expect much higher growth to give a company a true growth multiple. Where exactly the transition category hits on the market growth curve is therefore not driven solely by slowing revenue growth and varies company to company. It seems to be driven by some combination of the stage of the company’s market curve and the valuation of the company.

Uber and WeWork are transition companies. Uber, based on revenue growth, had matured fairly deep into its market curve. It grew gross booking 31% in its first quarter as a public company. On the other hand, WeWork showed 100%+ revenue growth in its S-1 in the first six months of 2019. Based on those revenue growth rates, Uber appeared to be far deeper into its market curve than WeWork, but WeWork’s valuation at the time, $47 billion, more than priced in the company’s growth potential despite the rapid growth rate. With a large-cap growth valuation, investors want to see beyond large-cap growth potential that would have enabled WeWork to transcend to the holy grail of technology investments — the compounder. Instead, investors only saw rapid growth with poor margins and WeWork got a bailout.

The transition category is difficult to invest in because the only way for the investor to continue to see returns is if the company in question can become a compounder with solid growth and a high return on invested capital — a status reserved for truly rare companies. If the transition company can’t become a compounder, the investor has to believe the company can build into another market in the near term that can augment growth, move the company back down into the growth category of the tech investment framework, and ultimately have that new market become the core business of the company. More often than not, transition companies turn into tech value plays, which are not good long-term investments.

Transition companies can live in this category for several years on the path to proving compounder status or falling into the value category.

Value Tech

There is no such thing as a value company in tech. We’ve lived by this mantra for more than 10 years and still believe it true today.

When technology companies stop growing, best case it’s because the underlying market is mature but stable with underwhelming growth prospects. More often than not, the company’s technology is obsolete and the market is ripe for disruption. The value category in tech is comprised of companies with modest to poor revenue growth rates — generally 20% or below — and disappointing profit margins with minimal chance for improvement.

Tech companies that fit into the value category live in a sort of purgatory. There is minimal opportunity to reaccelerate growth in their existing markets, and investors aren’t likely to be excited to give value tech companies more capital to explore new markets. Modest margins also make it difficult for the companies to self-fund exploration into new markets. On top of capital constraints, retaining tech talent is difficult with a languishing stock price.

Capital accrues to winners in tech, per Alfred Lin. Capital accrual comes in the form of both investment and profit for tech, particularly in Internet-distributed companies where winners often take all. Locality encourages winner-take-all dynamics, and the Internet makes the world local.

Value tech companies will not accrue capital in the form of profit or investment for seeking new market opportunities, making them long-term losers. Investors should only consider tech companies in the value category as shorter-term trades, if at all.

Best to just avoid value tech companies because there is really no such thing.

Compounders

Compounders are the true unicorns of tech investing — the exceptional company that you should invest in at a fair price and hold indefinitely. Morgan Stanley defines a compounder as ”high quality, franchise businesses, ideally with recurring revenues, built on dominant and durable intangible assets, which possess pricing power and low capital intensity.”

We define tech compounders internally as market-leading companies with high profit margins driven by a differentiated product and defensible business model. Tech compounders also require a culture that embraces constant innovation at a relentless pace. Because of the competitive position of compounders, they often also have solid to strong growth in the low-double digits y/y even at relative maturity. These companies generate significant free cash flow that can be reinvested in the business at high rates of return and/or returned to shareholders.

One or two companies often win dominant positions in local markets. For example, most towns or neighborhoods only have one or two pizza places, not five or six. Over the long term, customers will gravitate to whichever has the best product, creating a winner that takes most or all.

The Internet made the world local. As a result, compounders almost always show winner-take-all dynamics in the markets they compete in. Software businesses demonstrate this most obviously. Tech businesses that require physical infrastructure can easily make states and countries local instead of towns or neighborhoods, but tech infrastructure companies deal with more friction to make the world local than software companies.

Investors can easily fool themselves about the progress of a company at every stage, but because there are so few compounders, this category is especially easy to incorrectly assign. As a rule, if you think you have a compounder, you probably don’t.

If you do have a compounder, it should stand alongside companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook.